Optimising the CSS Processor (ANTS and algorithms)

The Production Team at work have started using my best-practices-rules-validating LESS CSS Processor (which utilises dotLess). This is excellent news for me! And frankly, I think it's excellent news for them! :D

This all ties in with a post I wrote at the start of the year (Non-cascading CSS: A revolution!), a set of rules to write maintainable and genuinely reusable stylesheets. I gave a presentation on it at work and one of the Lead Devs on Production recently built the first site using the processor (I've used it for this blog but the styling here is hardly the most complex). Now that it's been proven, it's being used on another build. And a high-profile one, at that. Like I said, exciting times!

However, during the site-build process there are periods where the routine goes tweak styles, refresh, tweak styles, refresh, tweak styles, lather, rinse, repeat. And when the full set of stylesheets starts getting large, the time to regenerate the final output (and perform all of the other processing) was getting greater and making this process painful.

The good news is that now that the project is being used in work, I can use some of work's resources and toys to look into this. We allocated a little time this sprint to profile the component and see if there are any obvious bottlenecks that can be removed. The golden rule is you don't optimise until you have profiled. Since we use ANTS Performance Profiler at work, this seemed like an excellent place to start.

March of the ANTS

The ANTS Performance Profile is a great bit of kit for this sort of thing. I prepared an executable to test that would compile stylesheets from the new site in its current state. This executable had a dependency on the processor code - the idea is I choose something to optimise, rebuild the processor, rebuild the test executable and re-run the profiler.

Things take much longer to run in the profiler than they would otherwise (which is to be expected, the profiler will be tracking all sorts of metrics as the code runs) but performance improvements should mean that the execution time decreases on subsequent runs. And, correspondingly, the component will run more quickly when not in the profiler, which is the whole point of the exercise!

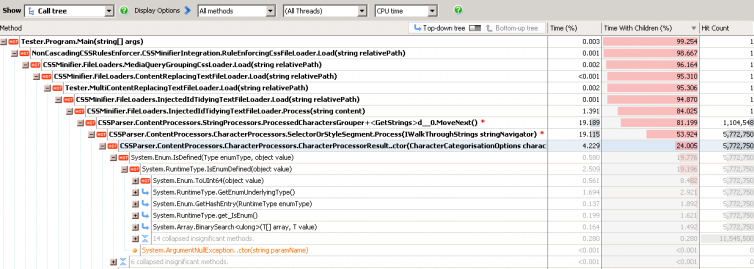

So I point the profiler at the executable and the results look like the following..

(I shrank the screenshot to get it to fit on the page properly, if you can't read it then don't worry, I'm about to explain the highlights).

What we're looking at is a drilling-down of the most expensive methods. I've changed the Display Options to show "All Methods" (the default is "Only methods with source") so I can investigate as deep as I want to*. This view shows method calls as a hierarchy, so Tester.Program.Main is at the top and that calls other methods, the most expensive of which is the NonCascadingCSSRulesEnforcer.CSSMinifierIntegration.RulesEnforcingCssFileLoader.Load call. While the call to Main accounted for 99.254% of the total work, the call to this Load method accounted for 98.667% (looking at the "Time With Children (%)" column). This means that Main's own work and any other method calls it made account for a very small amount of total work done.

* (If the PDB files from a build are included in the executable folder then the profiler can use these to do line-by-line analysis in a window underneath the method call display shown above. To do this, "line-level and method-level timings" have to be selected when starting the profiling and the source code files will have to be available to the profiler - it will prompt for the location when you double-click on a method. If you don't have the PDB files or the source code then methods can be decompiled, but line level details will not be available).

Method calls are ordered to show the most expensive first, the "HOT" method. This is why that Load method appears first inside the results for Main, it accounts for most of the work that Main does.

So the first easy thing to do is to look for methods whose "HOT" method's "Time With Children" is much lower, this could be an indication that the method itself is quite expensive. It could also mean that it calls several methods which are all quite expensive, but this can still often be a good way to find easy wins.

What jumps out at me straight away is the CharacterProcessorResult..ctor (the class constructor) and its children account for 24.005% of the total run time, with Enum.IsDefined (and its children) accounting for 19.776%. The Enum.IsDefined call is to ensure that a valid enum value is passed to the constructor. Enum.IsDefined uses reflection if you look far enough down, I believe. A few calls to this method should be no big deal, but an instance of this class is used for every stylesheet character that is parsed - we can see that the constructor is called 5,772,750 times (the "Hit Count"). So replacing Enum.IsDefined with if statements for all of the possible enum options should speed things up considerably. Incidentally, 5,772,750 seems like a lot of character parse attempts, it's certainly a lot more content than exists in the source stylesheets, I'll address this further down..

Looking at the screenshot above, there are two other "jumps" in "Time With Children" - one going from ProcessedCharacterGrouped+

More easy optimisations

After making the change outlined above (removing the Enum.IsDefined call from the CharacterProcessorResult constructor), the profiler is re-run to see if I can find any more small-change / big-payoff alterations to make. I did this a few times and identified (and addressed) the following -

The StringNavigator.CurrentCharacter property was being marked as taking a lot of time. This was surprising to me since it doesn't do much, it only returns a character with a particular index from the content string that is being examined. However, the hit count was enormous as this could be called multiple times for each character being examined - so if there were nearly 6m character results, there were many more StringNavigator.CurrentCharacter requests. I changed the string to a character array internally thinking that access to it might be quicker but it didn't make a lot of difference. What did make a difference was to extract the CurrentCharacter value in the StringNavigator's constructor and return that value directly from the property, reducing the number of character array accesses required. What made it even better was to find any method that requested the CurrentCharacter multiple times and change them to request it once, store it in a local variable and use that for subsequent requests. Although each property access is very cheap individually, signficantly reducing the total number of property requests resulted in faster-running code. This is the sort of thing that would have felt like a crazy premature optimisation if I didn't have the profiler highlighting the cost!

The InjectedIdTidyingTextFileLoader's TidySelectorContent method spent a lot of its time in a LINQ "Any" call. The same enumerable data was being looped through many times - changing it to a HashSet (and using the HashSet's Contains method) made this much more efficient. (The HashSet uses the same technique as the Dictionary's key lookup which, as I've written about before in The .Net Dictionary is FAST!, has impressive performance).

The CategorisedCharacterString's constructor also had an Enum.IsDefined call. While this class is instantiated much less often than the CharacterProcessorResult, it was still in the hundreds of thousands range, so it was worth changing too.

The StringNavigator had a method "TryToGetCharacterString" which would be used to determine whether the current selector was a media query (does the current position in the content start with "@media") or whether a colon character was part of a property declaration or part of a pseudo class in a selector (does the current position in the content start with ":hover", ":link", etc..) - but in each case, we didn't really want the next n characters, we just wanted to know whether they were "@media", ":hover" or whatever. So replacing "TryToGetCharacterString" with a "DoesCurrentContentMatch" method meant that less work would be done in the cases where no match was found (this method would exit "early" as soon as it encountered a character than didn't match what it was looking for).

Finally, the ProcessedCharactersGrouper has an array of "CharacterTypesToNotGroup". This class groups adjacent characters that have the same CharacterCategorisationOptions into strings - so if there are characters 'a', '.', 't', 'e', 's', 't' which are all of type "SelectorOrStyleProperty" then these can be grouped into a string "a.test" (with type "SelectorOrStyleProperty"). However, multiple adjacent "}" characters are not combined since they represent the terminations of different style blocks and are not related to each other. So "CloseBrace" is one of the "CharacterTypesToNotGroup" entries. There were only three entries in this array (CloseBrace, OpenBrace and SemiColon). When deciding whether to group characters of the same categorisation together, replacing the LINQ "Contains" method call with three if statements for the particular values improved the performance. I believe that having a named array of values made the code more "self documenting" (it is effectively a label that describes why these three values are being treated differently) but in this case the performance is more important.

The end result of all of these tweaks (all of which were easy to find with ANTS and easy to implement in the code) was a speed improvement of about 3.7 times (measuring the time to process the test content over several runs). Not too shabby!

Algorithms

I still wasn't too happy with the performance yet, it was still taking longer to generate the final rules-validated stylesheet content than I wanted.

Before starting the profiling, I had had a quick think about whether I was doing anything too stupid, like repeating work where I didn't need to. The basic process is that

- Each .less file is loaded (any @imports will be "flattened" later, the referenced content is loaded at this point, though, so that it can be put in the place of the @import later on)

- Each file gets fed through the file-level rules validators

- Source Mapping Marker Ids are inserted

- The "@import flattening" occurs to result in a single combined content string

- This content is fed through the dotLess processor (this translates LESS content into vanilla CSS and minifies the output)

- This is fed through the combined-content-level rules validators

- Any "scope-restricting html tags" are removed

- Source Mapping Marker Ids are tidied

When each file gets fed through the file-level rules validators, the source content is parsed once and the parsed content passed through each validator. So if there are multiple validators that need to be applied to the same content, the content is only parsed once. So there's nothing obvious here.

What is interesting is the "Source Mapping Marker Ids". Since the processor always returns minified content and there is no support for CSS Source Mapping across all browsers (it looks like Chrome 28+ is adding support, see Developing With Sass and Chrome DevTools) I had my processor try to approximate the functionality. Say you have a file "test.css" with the content

html

{

a.test

{

color: #00f;

&:hover { color: #00a; }

}

}

the processor rewrites this as

#test.css_1, html

{

#test.css_3, a.test

{

color: #00f;

#test.css_6, &:hover { color: #00a; }

}

}

which will eventually result (after all of the steps outlined above have been applied) in

#test.css_3,a.test{color:#00f}

#test.css_6,a.test:hover{color:#00a}

This means that when you examine the style in a browser's developer tools, each style can be traced back to where the selector was specified in the source content. A poor man's Source Mapping, if you like.

The problem is that the LESS compiler will actually translate that source-with-marker-ids into

#test.css_1 #test.css_3,

#test.css_1 a.test,

html #test.css_3,

html a.test { color: #00f; }

#test.css_1 #test.css_3 #test.css_6,

#test.css_1 #test.css_3:hover,

#test.css_1 a.test #test.css_6,

#test.css_1 a.test:hover,

html #test.css_3 #test.css_6,

html #test.css_3:hover,

html a.test #test.css_6,

html a.test:hover { color: #00a; }

That's a lot of overhead! There are many selectors here that aren't required in the final content (such as "html #test.css_3", that is neither specific enough to be helpful in the developer tools nor a real style that applies to actual elements). This is what the "Source Mapping Marker Ids are tidied" step deals with.

And this explains why there were nearly 6 million characters being parsed in the stylesheets I've been testing! The real content is getting bloated by all of these Source Mapping Marker Ids. And every level of selector nesting makes it significantly worse.

(To convince myself that I was thinking along the right lines, I ran some timed tests with variations of the processor; disabling the rules validation, disabling the source mapping marker id injection, disabling the marker id tidying.. Whether or not the rules validation was enabled made very little difference. Disabling the marker id injection and tidying made an enormous difference. Disabling just the tidying accounted for most of that difference but if marker ids were inserted and not tidied then the content was huge and full of unhelpful selectors).

Addressing the problems: Limiting Nesting

Since nesting selectors makes things much worse, any way to limit the nesting of selectors could be a signficant improvement. But this would largely involve pushing back the "blame" onto users of the processor, something I want to avoid. There is one obvious way, though. One of the rules is that all stylesheets (other than Resets and Themes sheets) must be wrapped in a "scope-restricting html tag". This means that any LESS mixins or values that are defined within a given file only exist within the scope of the current file, keeping everything self-contained (and so enabling an entire file to be shared between projects, if that file contains the styling for a particular common component, for example). Any values or mixins that should be shared across files should be declared in the Themes sheet. This "html" selector would result in styles that are functionally equivalent (eg. "html a.test:hover" is the same as "a.test:hover" as far as the browser is concerned) but the processor actually has a step to remove these from the final content entirely (so only "a.test:hover" is present in the final content instead of "html a.test:hover").

So if these "html" wrappers will never contribute to the final content, having marker ids for them is a waste of time. And since they should be present in nearly every file, not rewriting them with marker ids should significantly reduce the size of the final content.

Result: The test content is fully processed about 1.8x as fast (times averaged over multiple runs).

Addressing the problems: Shorter Marker Ids

Things are really improving now, but they can be better. There are no more easy ways to restrict the nesting that I can see, but if the marker ids themselves were shorter then the selectors that result from their combination would be shorter, meaning that less content would have to be parsed.

However, the marker ids are the length they are for a reason; they need to include the filename and the line number of the source code. The only way that they could be reduced would be if the shortened value was temporary - the short ids could be used until the id tidying has been performed and then a replacement step could be applied to replace the short ids with the full length ids.

To do this, I changed the marker id generator to generate the "real marker id" and stash it away and to instead return a "short marker id" based on the number of unique marker ids already generated. This short id was a base 63* representation of the number, with a "1" prefix. The reason for the "1" is that before HTML5, it was not valid for an id to begin with a number so I'm hoping that we won't have any pages that have real ids that these "short ids" would accidentally target - otherwise the replacement that swaps out the short ids for real ids on the stylesheets might mess up styles targetting real elements!

* (Base 63 means that the number may be represented by any character from the range A-Z, a-z, 0-9 or by an underscore, this means that valid ids are generated to ensure that characters are not pushed through the LESS compiler that would confuse it).

The earlier example

html

{

a.test

{

color: #00f;

&:hover { color: #00a; }

}

}

now gets rewritten as

html

{

#1A, a.test

{

color: #00f;

#1B, &:hover { color: #00a; }

}

}

which is transformed into

html #1A,

html a.test {

color: #00f;

}

html #1A #1B,

html #1A:hover,

html a.test #1B,

html a.test:hover {

color: #00a;

}

This is a lot better (combining the no-markers on the "html" wrapper and the shorter ids). There's still duplication present (which will get worse as styles are more deeply nested) but the size of the content is growing much less with the duplication.

Result: The test content is fully processed about 1.2x faster after the above optimisation, including the time to replace the shortened ids with the real marker ids.

Conclusion

With the ANTS-identified optimisations and the two changes to the algorithm that processes the content, a total speed-up of about 7.9x has been achieved. This is almost an order of magnitude for not much effort!

In real-world terms, the site style content that I was using as the basis of this test can be fully rebuilt from source in just under 2 seconds, rather than the almost 15 seconds it was taking before. When in the tweak / refresh / tweak / refresh cycle, this makes a huge difference.

And it was interesting to see the "don't optimise before profiling" advice in action once more, along with "avoid premature optimisation". The places to optimise were not where I would have expected (well, certainly not in some of the cases) and the last two changes were not the micro-optimisations that profilers lead you directly to at all; if you blindly follow the profiler then you miss out on the "big picture" changes that the profiler is unaware of.

Posted at 20:37

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)