Non-cascading CSS: A revolution!

("Barely-cascading CSS: A revolution!", "Barely-cascading CSS: A revolution??")

This post was inspired by what I read at www.lispcast.com/cascading-separation-abstraction who in turn took some inspiration from 37signals.com/svn/posts/3003-css-taking-control-of-the-cascade.

Part of what really clicked for me was this

The value of a CSS property is determined by these factors:

- The order of CSS imports

- The number of classes mentioned in the CSS rule

- The order of rules in a particular file

- Any inherits settings

- The tag name of the element

- The class of the element

- The id of the element

- All of the element's ancestors in the HTML tree

- The default styles for the browser

combined with

By using nested LESS rules and child selectors, we can avoid much of the pain of cascading rules. Combining with everything else, we define our styles as mixins (and mixins of mixins)..

and then the guidelines

- Only bare (classless + non-nested) selectors may occur in the reset.

- No bare selectors may occur in the LESS rules.

- No selector may be repeated in the LESS rules.

along with

The box model sucks.. And what happens when I set the width to 100%? What if a padding is cascaded in? Oops.

I propose to boycott the following properties: ..

I must admit that when I first read the whole article I thought it was quite interesting but it didn't fully grab me immediately. But it lingered in the back of my mind for a day or two and the more I thought about it, the more it took hold and I started to think this could offer a potentially huge step forward for styling. Now, I wish I'd put it all together!

What I really think it could possibly offer as the holy grail is the ability to re-use entire chunks of styling across sites. At work this is something that has been posited many times in the past but it's never seemed realistic because the styles are so intermingled between layout specific to one site and the various elements of a control. So even in cases where the basic control and its elements are similar between sites, it's seemed almost implausible to consistently swap style chunks back and forth and to expect them to render correctly, no matter how careful and thoughtful you are with constructing the styles. But I realise now that this is really due almost entirely to the complex cascading rules and its many knock-on effects!

So I'm going to present my interpretation of the guidelines. Now, these aren't fully road-tested yet, I intend to put them to use in a non-trivial project as soon as I get the chance so this is just my initial plan-of-attack..

My interpretation

I'm going to stick with LESS as the CSS processor since I've used it in the past.

A standard (html5-element-supporting) reset sheet is compulsory, only bare selectors may be specified in it

A single "common" or "theme" sheet will be included with a minimum of default styles, only bare selectors may be specified in it

No bare selectors may occur in the non-reset-or-theme rules (a bare selector may occur within a nested selector so long as child selectors are strictly used)

Stylesheets are broken out into separate files, each with a well-defined purpose

All files other than the reset and theme sheets should be wrapped in a body "scope"

No selector may be repeated in the rules

All measurements are described in pixels

Margins, where specified, must always be fully-defined

Border and Padding may not be combined with Width

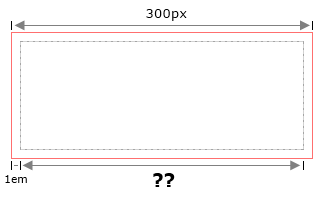

(Above) This is what I'm trying to avoid!

A standard (html5-element-supporting) reset sheet is compulsory

This is really to take any browser variation out of the equation. You can start by thinking it's something along the lines of "* { margin: 0; padding: 0; }" and then think some more about it and then just go for Eric Meyer's html5-supporting reset. That's my plan at least! :)

A single "common" or "theme" sheet will be included with a minimum of default styles, only bare selectors may be specified in it

I was almost in two minds about this because it feels like it is inserting a layer of cascading back in, but I think there should be one place to declare the background colour and margin for the body, to set the default font colour, to set "font-weight: bold" on strong tags and to set shared variables and mixins.

No bare selectors may occur in the non-reset-or-theme rules (a bare selector may occur within a nested selector so long as child selectors are strictly used)

Bare selectors (eg. "div" rather than "div.AboutMe", or even "div.AboutMe div") are too generic and will almost certainly end up polluting another element's style cascade, which we're trying to avoid.

The reason for the exception around child selectors is that this may be used in places where classes don't exist on all of the elements to be targeted. Or if the bullet point type for a particular list is to be altered, we wouldn't expect to have to rely upon classes - eg.

<div class="ListContainer">

<ul>

<li>Item</li>

<li>Another Item</li>

</ul>

</div>

may be styled with

div.ListContainer

{

> ul > li { list-style-type: square; }

}

This would not affect the second level of items. So if the markup was

<div class="ListContainer">

<ul>

<li>

Item

<ul>

<li>Sub Item<li>

</ul>

</li>

<li>Another Item</li>

</ul>

</div>

then "Sub Item" will not get the "square" bullet point from the above styles. And this is progress! This is what we want, for styles to have to be explicit and not possibly get picked up from layer after layer of possible style matches. If we didn't use child selectors and we didn't want the nested list to have square markers then we'd have to add another style to undo the square setting.

Or, more to point (no pun intended!), if we want to specify a point style for the nested list then adding this style will not be overriding the point style from the outer list, it will be specifying it for the first time (on top of the reset style only), thus limiting the number of places where the style may have come from.

In order for the inner list to have circle markers we need to extend the style block to

div.ListContainer

{

> ul > li

{

list-style-type: square;

> ul > li

{

list-style-type: circle

}

}

}

Stylesheets are broken out into separate files, each with a well-defined purpose

This is for organisational purposes and I imagine that it's a fairly common practice to an extent, but I think it's worth taking a step further in terms of granularity and having each "chunk" or control in its own file. Since pre-processing is going to be applied to combine all of the files together, why not have loads of them if it makes styles easier to organise and find!

I've just had a quick look at Amazon to pick out examples. I would go so far as to have one file NavTopBar.less for the navigation strip across the top, distinct from the NavShopByDepartment.less file. Then a LayoutHomePage file would arrange these elements, with all of the other on that page.

The more segregated styles are, the more chance (I hope!) that these file-size chunks could be shared between projects.

One trick I've been toying with at work is to inject "source ids" into the generated css in the pre-processing step so that when the style content is all combined, LESS-compiled and minified, it's possible to determine where the style originally came from.

For example, I might end up with style in the final output like

#AboutMe.css_6,div.ListContainer>ul>li{list-style-type:square}

where the "#AboutMe.css_6" id relates not to an element but line 6 of the "AboutMe.css" file. It's a sort of poor man's version of Source Mapping which I don't believe is currently available for CSS (which is a pity.. there's a Mozilla feature request for it, though: CSSSourceMap).

I haven't decided yet whether this should be some sort of debug option or whether the overhead of the additional bytes in the final payload are worth the benefit for debugging. There's an argument that if the styles are broken into files and all have tightly targeted selectors then it should be relatively easy to find the source file and line, but sometimes this doesn't feel like the case when you go back to a project six months after you last looked at it!

Another example of a file with a "well-defined purpose" might be to apply a particular grid layout to a particular template, say "CheckoutPageLayout". This would arrange the various elements, but each of the elements within the page would have their own files.

All files other than the reset and theme sheets should be wrapped in a body scope

This is inspired by the Immediately Invoked Function Expression pattern used in Javascript to forcibly contain the scope of variables and functions within. Since we can do the same thing with LESS values and mixins, I thought it made sense to keep them segregated, this way if the same name is used for values or mixins in different files, they won't trample on each other toes.

The idea is simply to nest all statements within a file inside a "body { .. }" declaration - ie.

body

{

// All the content of the file goes here..

}

This will mean that the resulting styles will all be preceded with the "body" tag which adds some bloat to the final content, but I think it's worth it to enable this clean scoping of values and mixins. Any values and mixins that should be shared across files should be defined in the "common" / "theme" sheet.

Just as a quick reminder, the following LESS

@c = red;

.e1 { color: @c; }

body

{

@c = blue;

.e2 { color: @c; }

}

.e3 { color: @c; }

will generate this CSS

.e1 { color: red; }

body .e2 { color: blue; }

.e3 { color: red; }

The @c value inside the body scope applies within that scope and overrides the @c value outside of the scope while inside the scope. Once back out of the scope (after the "body { .. }" content), @c still has the value "red".

It's up for debate whether this definitely turns out to be a good idea. Interesting, so far I've not come across it anywhere else, but it really seems like it would increase the potential for sharing files (that are tightly scoped to particular controls, or other unit of layout / presentation) between projects.

Update (4th June 2013): I've since updated this rule to specify the use of the html tag rather than body as I've written a processor that will strip out the additional tags injected (see Extending the CSS Minifier) and stripping out body tags would mean that selectors could not be written that target elements in a page where a particular class is specified on the body tag.

No selector may be repeated in the rules

In order to try to ensure that no element gets styles specified in more places than it should (that means it should be set no more frequently than in the resets, in the "common" / "theme" sheet and then at most by one other specific selector), class names should not be repeated in the rules.

With segregation of styles in various files, it should be obvious which single file any given style belongs in. To avoid duplicating a class name, LESS nesting should be taken advantage of, so the earlier example of

div.ListContainer

{

border: 1px solid black;

> ul > li { list-style-type: square; }

}

is used instead of

div.ListContainer { border: 1px solid black; }

div.ListContainer > ul > li { list-style-type: square; }

and where previously class names might have been repeated in a CSS stylesheet because similar properties were being set for multiple elements, this should now be done with mixins - eg. instead of

div.Outer, div.Inner

{

float: left;

width: 100%;

}

div.Inner { border: 1px solid black; }

we can use

.FullWidthFloat ()

{

float: left;

width: 100%;

}

div.Outer

{

.FullWidthFloat;

}

div.Inner

{

.FullWidthFloat;

border: 1px solid black;

}

This is clearly straight from lispcast's post, it's a direct copy-and-paste of their guideline 2!

We have to accept that this still can't prevent a given element from having styles set in multiple places, because it's feasible that multiple selectors could point to the same element (if an element has multiple classes then there could easily be multiple selectors that all target it) but this is definitely a good way to move towards the minimum number of rules affecting any one thing.

All measurements are described in pixels

I've been all round the houses in the last few years with measurement units. Back before browsers all handled content-resizing with zoom functionality (before Chrome was even released by Google to shake up the web world) I did at least one full site where every single measurement was in em's - not just the font sizes, but the layout measurements, the borders, the image dimensions, everything! This mean that when the font was sized up or down by the browser, the current zooming effect we all have now was delivered. In all browsers. Aside from having to do some lots of divisions to work out image dimensions (and remembering what the equivalent of 1px was for the borders!), this wasn't all that difficult most of the time.. but where it would become awkward was if a containing element had a font-size which would affect the effective size of an em such that the calculations from pixel to em changed. In other words, cascading styles bit me again!

In more common cases, I've combined pixels and ems - using ems in most places but pixels for particular layout arrangements and images.

But with the current state of things, with the browsers handling zooming of the content regardless of the units specified, I'm seriously suggesting using pixels exclusively. For one thing, it will make width calculations, where required, much much simpler; there can't be any confusion when trying to reason about distances in mixed units!

I'm going to try to pixels-only and see how it goes!

One pattern that I've seen used is to combine "float: left;" and "width: 100%;" when an element has children that are floated, but the element must expand to fully contain all of those children. In the majority of cases I see it used in site builds where I work, the elements that have been floated could have had "display: inline-block" applied instead to achieve the same layout - the use of floats is left over from having to fully support IE6 which wouldn't respect "inline-block" (it was less than a year ago that we managed to finally shackle those IE6 chains! Now it's a graceful-degradation-only option, as I think it should be).

So there's a chance that some allowances will have to be made for 100% widths, but I'm going to start off optimistic and hope that it's not the case until I'm proven wrong (either by myself or someone else trying these rules!).

Update (22nd January 2013): Although I'm currently still aiming for all-pixel measurements for elements, after reading this article The EMs have it: Proportional Media Queries FTW! I think I might get sold on the idea of using em's in media queries.. it seems like it would be an ideal to work with browsers that have been zoomed in sufficiently that they'd look better moving the next layout break point. I need to do some testing with mobile or tablet devices, but it sounds intriguing!

Margins, where specified, must always be fully-defined

This is straight from the lispcast post; it just means that if you specify a margin property that you should use the "margin" property and not "margin-left", "margin-top", etc.. The logic being that if you specify only "margin-left", for example, then the other margin sizes are inherited from the previous declaration that was applied (even if that's only the reset files). The point is that the style is split over multiple declarations and this is what we're trying to avoid.

So instead of

margin-left: 4px;

specify

margin: 0 0 0 4px;

If you require a 4px margin top, bottom, left and right then

margin: 4px;

is fine, the point is to ensure that every dimension is specified at once (which the above will do), specifying the dimensions individually within a single margin value is only required if different sides need different margin sizes!

Border and Padding may not be combined with Width

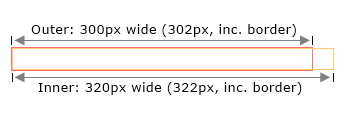

This is also heavily inspired by the lispcast post, it's intended to avoid box model confusion. When I first read it, I had a blast-from-the-past shiver go through me from the dark days where we had to deal with different box models between IE and other browsers but this hasn't been an issue with the proper doc types since IE...6?? So what really concerns us is if we have

<div class="outer">

<div class="inner">

</div>

</div>

and we have the styles

.outer { width: 300px; margin: 0; border: 1px solid black; padding: 0; }

.inner { width: 300px; margin: 0; border: 1px solid black; padding: 10px; }

then we could be forgiven for wanting both elements to be rendered with the same width, but we'll find the "inner" element to appear wider than the "outer" since the width within the border is the content width (as specified by the css style) and then the padding width on top of that.

Another way to illustrate would be the with the styles

.outer { width: 300px; margin: 0; border: 1px solid black; padding: 0; }

.inner { width: 100%; margin: 0; border: 1px solid black; padding: 10px; }

Again, the "inner" element juts out of the "outer" since the padding is applied around the 100% width (in this example, the 100% equates to the 300px total width of the "outer" element) which seems counter-intuitive.

So what if we don't use padding at all?

In an ideal world - in terms of the application of styling rules - where an element requires both an explicit width and a padding, this could be achieved with two elements; where the outer element has the width assigned and the inner element has the padding. But, depending upon how we're building content, we mightn't have the ability to insert extra elements. There's also a fair argument that we'd adding elements solely for presentation rather than semantic purpose. So, say we have something like

<div class="AboutMe">

<h3>About</h3>

<p>Content</p>

</div>

instead of specifying

div.AboutMe { width: 200px; padding: 8px; }

maybe we could consider

div.AboutMe { width: 200px; }

div.AboutMe > h3 { margin: 8px 8px 0 8px; }

div.AboutMe > p { margin: 0 8px 8px 8px; }

This would achieve a similar effect but there is a certain complexity overhead. I've used child selectors to indicate the approach that might be used if there were more complicated content; if one of the child elements was a div then we would want to be certain that this pseudo-padding margin only applied to the child div and not one of its descendent divs (this ties in with rule 3's "a bare selector may occur within a nested selector so long as child selectors are strictly used" proviso).

And the border issue hasn't been addressed; setting a border can extend the total rendered width beyond the width specified by css as well! (Also indicated in the example image above).

So I'm tentatively suggesting just not having any styles apply to any element that specifies width and padding and/or border.

This is one of the rules that I feel least confident about and will be considering retracting when I manage to get these into use in a few projects. If the benefit isn't sufficient to outweigh the cost of thinking around it, then it may have to be put out to pasture.

Linting

As I've said, I'm yet to fully use all of these rules in anger on a real, sizable project. But it's something I intend to do very soon, largely to see how well they do or don't all work together.

Something I'm contemplating looking into is adding a pre-processing "lint" step that will try to confirm that all of these rules have been followed. Inspired by Douglas Crockford's JsLint (and I've only just found out that "lint" is a generic term, I didn't know until now where it came from! See "Lint" on Wikipedia).

It could be configured such that if a rule was identified to have not been followed, then an error would be returned in place of any style content - that would ensure that I didn't ignore it!

I'm not sure yet how easy it will or won't be to check for all of these rules, but I'm definitely interested in finding out!

Hopefully I'll post back with a follow-up at some point, possibly with any interesting pre-processing code to go along with it. I think the only way to determine the validity of these rules is with the eating of a whole lot of my own dog food :)

Update (4th June 2013): I've written a couple of related posts - see the Non-cascading CSS: The follow-up and Extending the CSS Minifier. The first has a couple of amendments I've made to these rules after putting them into practice and the second has information about how my CSS Minifier project now has support for injecting into the compiled output the "source ids" mentioned in this post, along with a way to implement rule 5 (html-tag-scoping). I also intend to write a few posts about the mechanisms used to implement these processing steps starting with Parsing CSS.

Posted at 23:04

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)