I didn't understand why people struggled with (.NET's) async

Long story short (I know that some readers love a TL;DR), I have almost always worked with async/await in C# projects where it's been async from top-to-bottom and so I've rarely tried to start integrating async code into a large project that is primarily non-async. Due to this, I have never encountered any async problems.. so I've occasionally wondered "why would people be worried about getting deadlocks?"

Recently, this changed and I wanted to start integrating components that use async methods into a big project that doesn't. And it didn't take long until I got a hanging application!

Before I get to my story (and my solution), let me quickly recap what all the fuss is about.

What is "async" and why is it good?

To put things into context, I'm talking about a web application - code that hosts a website and spend 99% of its day "read only" and just rendering pages for people.

These do not tend to be computationally-intensive applications and if a page is slow to render then it's probably because the code is waiting for something.. like a database call to complete or an external cache request or the loading of a file.

Within IIS, when an ASP.NET application is hosted and is responding to requests, the simple model for synchronous code is that each request is allocated a thread to work on and it will keep hold of that thread for the duration of the request. A thread is an operating system construct and it occupies some resources - in other words, they're not free and, given the choice, we would like to need less of them rather than more of them. The threads in .NET are an abstraction over OS threads but to avoid getting too far off course, we'll think of them as being equivalent because they're close enough for the purposes of this post.

This model is very easy to understand but it's also easy to see how it could be quite wasteful. If the majority of our web server requests spend much of their time waiting for something external (database, other network I/O, local file system, etc..) then do we really need to tie up a thread for that time? Couldn't we free it up for another request (that isn't waiting for something external) to use and then try to get it back when whatever we're waiting on has finished doing its thing?

This is essentially what async / await is trying to solve. It introduces a simple way for us to write code that can say "I'm doing something that will perform an asynchronous action now - I'm expecting to wait for a little bit and so you (the .NET hosting environment) can have my thread back for a little while".

(Before async / await, it was possible to do this but it was much more convoluted and you had to deal with code that might follow a tangled web of callbacks and you would have to manually pass around any references that you would want to access in those callbacks - it was possible to do but made for code that was harder to read and write and, thusly, was more likely to contain mistakes)

When the .NET environment deals with "await", the thread that the await call happened on will be free'd back up. Then, when the async work is completed, a thread will be given back to that request so that it can carry on doing its thing. You might be wondering "how does .NET know when the work has completed? Surely that requires another thread to monitor whether the external resource has responded and, if so, aren't we right back where we started because we're blocking threads?" This is what I thought when I was first learning about async / await (and so I happen to think that it's an entirely reasonable question!) but it's not the case. The operating system and its drivers expose ways to say (and I'm grossly simplifying again because it's only the gist that we need here, not the full nitty gritty) "start sending this network data and notify me when data starts coming back in response" (and similar mechanisms for other types of I/O). When that notification occurs, the .NET environment can provide a thread to the request that was awaiting and let it carry on.

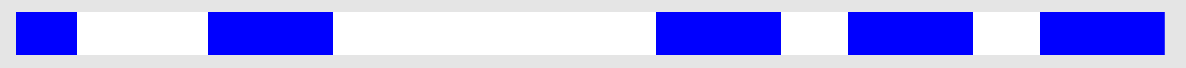

To try to illustrate this, imagine that the below image represents a web request. The blue parts are when computational work is being done on the thread and the white parts are when it's waiting on an external resource (like a database) -

At a glance, it's clear that there will be a lot of wasted time that a thread spends doing nothing (in a blocked state) if we're using the old model of "one thread for the entirety of the request". What might be slightly less easy to envisage, though, is just how many unnecessary threads that we might be occupying at any given time if all requests are like this.

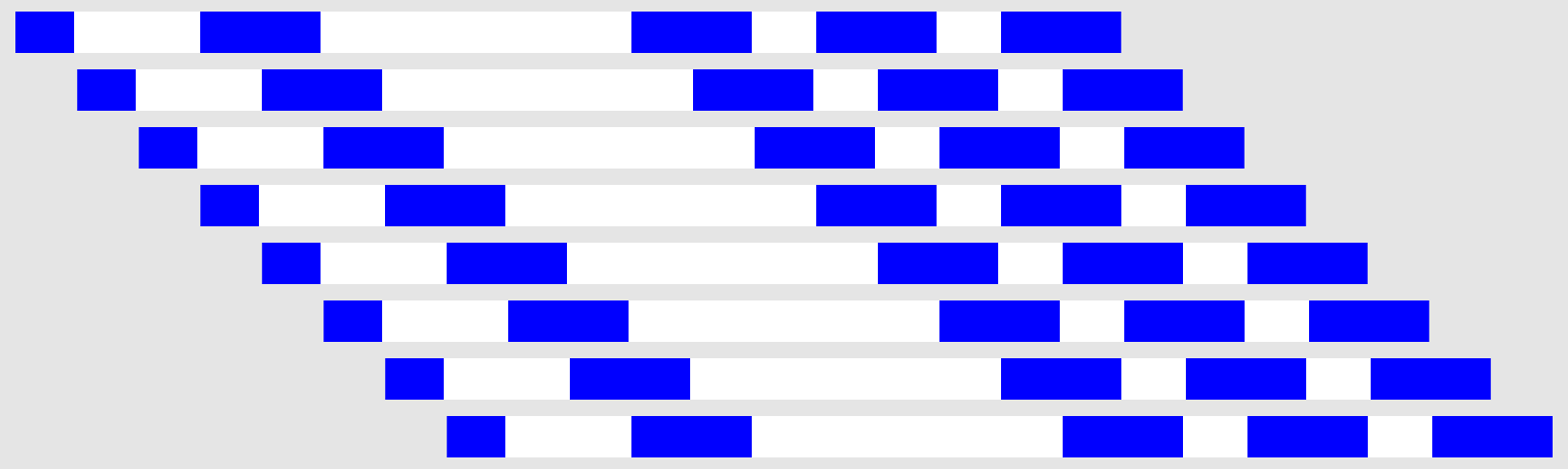

To try to illustrate that, I've stacked eight identical web requests representations on top of each other, staggered slightly in time -

Again, the blue represents time when each request is actively doing work and the white represents time when it's waiting for something (grey before a request is time before that request arrived at the server and grey after a request is time after it completed).

With the classic "one thread for the entirety of the request", we would be using up to eight threads for much of this time; initially only one thread would be active and then the second request would arrive and a second thread would get tied up and then a third thread would be used when the third request arrived and the threads wouldn't start getting free'd until the first request completed.

On the other hand, if we could free up a request's thread every time that it was waiting for an external resource then we would never require eight threads at any one time for these eight requests because there is no point in time when all eight of the requests are actively doing work at the exact same time.

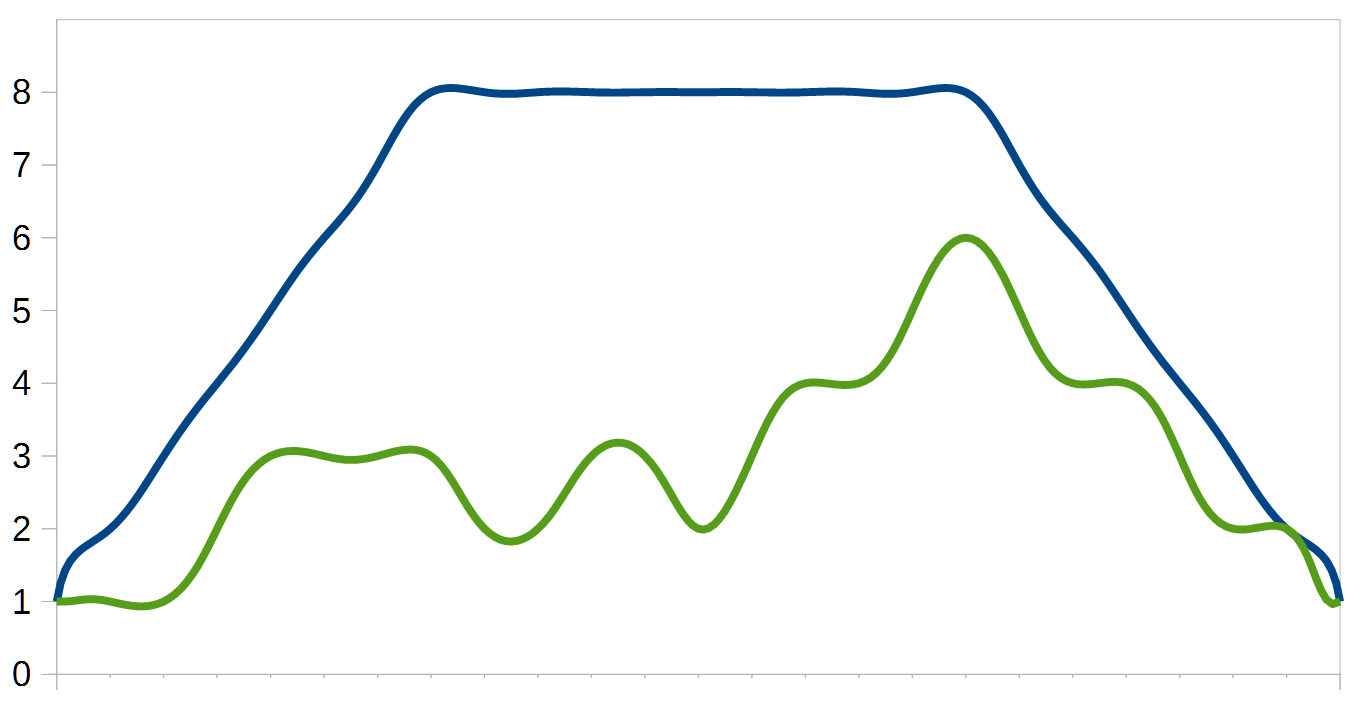

Time for a graph!

The blue line shows the number of active requests. If we have one-thread-per-request then that blue line also shows how many threads would be required to handle those requests.

The green line shows how many requests are actually doing work at any one time. If we are able to use the async / await model and only have web requests occupy threads while they're actively doing work then this is how many threads would be required. It's always less than the number of active requests and it's less than half for nearly all of the time in this example.

The async / await model means that we need to use less threads and that's less resources and that's a good thing!

A lightning overview of thread distribution

There was a lot of talk above of how "each request is allocated a thread to work" and "a thread will be given back to that request" and it's worth quickly reviewing how threads are created.

A thread in C# can be created using:

var thread = new Thread(nameOfMethodThatHasWorkToDoOnTheNewThread);

However, threads are a relatively expensive resource to new up and then discard over and over again and so .NET offers a way to "pool" threads. What this boils down to is that the ThreadPool framework class will maintain a list of threads and reuse them when someone needs one. This is used internally in many places within the .NET framework and it may be used like this:

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(nameOfMethodThatHasWorkToDoOnTheNewThread);

The ThreadPool will keep track of how many threads would need to exist at any given time to service all "QueueUserWorkItem" requests and it will track this over time so it can try to keep its pool at the optimum size for the application - too many means a waste of resources but too few means that it will take longer before the work requested via "QueueUserWorkItem" calls can be executed (if there is no thread free when a "QueueUserWorkItem" is made then that work will still happen but it will be queued up until the ThreadPool has a thread become free).

It would make for a fairly simple mental model if async / await always used the ThreadPool - if, when a request made an "await" call then it gave its current thread back to the ThreadPool and then, when the async work was completed, the request could continue on a thread provided by the ThreadPool. This would be straight forward and easy to understand and sometimes it is the case - Console Applications and Windows Services will work like this with async / await, for example. We can picture it a bit like this:

- A Windows Service receives a request and is given Thread "A" from the ThreadPool to start working on

- At some point, the request needs to perform an asynchronous action and so there is an "await" in the code - when this happens, Thread "A" is released back to the ThreadPool

- When that async task has completed, the request can carry on - however, Thread "A" was given to a different request while this request was waiting for the async work and so the ThreadPool gives it Thread "B"

- The request does some more synchronous work on Thread "B" and finishes, so Thread "B" is released back to the ThreadPool

Easy peasy.

Thread distribution troublemakers

However.. some project types get a bit possessive about their threads - when a request starts on one thread then it wants to be able to continue to use that thread forever. I suspect that this is most commonly known about WinForms projects where it was common to see code that looked like the following (that I have borrowed from a Stack Overflow answer):

private void OnWorkerProgressChanged(object sender, ProgressChangedArgs e)

{

// Cross thread - so you don't get the cross-threading exception

if (this.InvokeRequired)

{

this.BeginInvoke((MethodInvoker)delegate

{

OnWorkerProgressChanged(sender, e);

});

return;

}

// Change control

this.label1.Text = e.Progress;

}

With WinForms, you must never block the main thread because then your whole application window will go into a "not responding" state. So, if you wanted to start a process that is unlikely to complete instantly - such as a file upload - then you might have a component that performs the work on a different thread and that has events for "progress changed" (so that it can report {x}% complete) and "upload completed". When these events are raised, we'll want to update the UI of the application but there is a problem: when these callbacks are executed, they will be run on the thread that the file upload is running on and not the main UI thread. The reason that this is a problem is that UI components may only be updated by code that is running on the UI thread. The way around this is to check the "InvokeRequired" property on a UI component before trying to update any of the component's properties. If "InvokeRequired" returns false then it meant that the current thread is the UI thread and that no funny business was required. However, if it returns true then it means that the current thread is not the UI thread and that a special method "BeginInvoke" would have to be called, which was a way to say "please execute this code on the UI thread".

Eventually, people got used to this and would ensure that they used "InvokeRequired" and "BeginInvoke" when updating UI elements if they were dealing with code that might do some "background processing".

When async / await were introduced, though, one of the aims was to make it easy and neat and tidy to write async code - basically, to be able to write code that looked synchronous while still getting the benefits of being asynchronous. That meant trying to avoid code that looked like this:

private async void btnUpload_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

var filename = await UploadContent();

// Why do I need to do this?! I haven't (explicitly) fired

// up any new threads or anything! :S

if (this.InvokeRequired)

{

this.BeginInvoke((MethodInvoker)delegate

{

this.lblFilename.Text = filename;

});

return;

}

this.lblFilename.Text = filename;

}

Instead, it should just look like this:

private async void btnUpload_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

var filename = await UploadContent();

this.lblFilename.Text = filename;

}

The problem with this is that some magic will be required somewhere. If the ThreadPool is responsible for providing a thread to execute on after async work has completed, things are going to go wrong if it provides one thread to start the request on and a different thread to continue on after the async work has completed. It was fine for the Windows Service example request above to start on Thread "A" and then change to working on Thread "B" because Windows Services don't have limitations on what threads can and can't do, whereas WinForms UI components do.

The "magic" involved is that .NET provides a way for threads to be assigned a special "Synchronization Context". This is a mechanism that changes how async / await interacts with the ThreadPool and makes it possible for WinForms applications to say "When I await an asynchronous task and that task completes, I want to carry on my work on the same thread". This is why there is no need to check InvokeRequired / BeginInvoke when writing async event handlers for WinForms UI components.

One downside to this is that it puts constraints on how the ThreadPool can and can't distribute threads and means that it's not as free to optimise usage solely for efficiency and throughput. It also means that either the request's thread must remain allocated to the request until the request completes (negating one of the benefits of await / async) or the request may have to wait after an async call completes before the thread that it wants to continue on becomes free*.

* (I'm not actually sure which of these two options happens in real world use but it feels like the sort of thing that is an implementation detail of the framework and it would be best to not presume that it would be one or the other)

Update (Jan 2021): Stephen Cleary pointed out in a comment that actually the situation is not quite as bad as indicated with the pre-Core ASP.NET as it has some tricks up its sleeve regarding its synchronization context - the context can actually change threads, allowing it to fully release its current thread when it is awaiting something. This means that the impact on the ThreadPool is not as bad. I have, however, still encountered deadlocks in pre-Core ASP.NET and so it makes the issue less likely but not impossible. We're only talking about pre-Core ASP.NET here because ASP.NET on .NET Core doesn't have a synchronization context to worry about - see the section "Approach Five" further down in this post.

There is another downside, though, which is that it's quite easy to get into bother if you try to call async code from a non-async method - as I'm about to show you!

The classic deadlock (aka. "why has my application hung?")

This problem has been encountered so many times that a lot of async'ers recognise it straight away and there are plenty of questions on Stack Overflow about it. There is also good advice that is often repeated about how to prevent it. However, I think that it's particularly nasty because the code might not look hideously wrong at a glance but it will be able to cause your application to hang when it's run - not throw an exception (which at least makes it clear where something has gone wrong), but to just hang.

public class HomeController

{

public ActionResult Index()

{

return View(

GetTitleAsync().Result

);

}

private async Task<string> GetTitleAsync()

{

// This Task.Delay call simulates an async call that might go off to the

// database or other external service

await Task.Delay(1000);

return "Hello!";

}

}

When I encountered this problem, I was much deeper down the stack but the concept was the same -

- I was in code that was being called by an MVC action method and that method was not async

- I needed to call an async method

- I tried to access ".Result" on the task that I got back from the async method - this will block the current thread until the task completes

- The key factor: ASP.NET applications also have a special synchronization context, similar to the WinForms one in that it returns to the same thread after an async call completes

If you ran the code above then something like the following chain of events would occur:

- Thread "A" would be given to the request to run on and "Index" would be called

- Thread "A" would call "GetTitleAsync" and get a Task<string> reference

- Thread "A" would then request the ".Result" property of that task and would block until the task completed

- The "Task.Delay" call would complete and .NET would try to continue the "GetTitleAsync" work

- The ASP.NET synchronization context would require that work continue on Thread "A" and so the work would be placed on a queue for Thread "A" to deal with when it gets a chance (the "work" in this case is simply the line that returns the string "Hello!" but that code has to be executed somewhere)

And this is how we become stuck!

Thread "A" is waiting for the "GetTitleAsync" work to complete but the "GetTitleAsync" work can not complete until Thread "A" gets involved (which it can't because it's in a blocked state).

This is the problem and it seem oh-so-obvious if you know how async / await work and about the ASP.NET synchronization context and if you're paying close attention when you're writing this sort of code. But if you don't then you get a horrible runtime problem.

So let's look at solutions.

Approach one: Don't mix async and non-async code. This is good advice when starting new codes - begin with async and then it's async all the way down, no blocking of threads while accessing ".Result" and so no problem! However, with a big project it's not very helpful.

Approach two: Always use ".ConfigureAwait(false)". This is the oft-repeated good advice that I mentioned earlier. As a rule of thumb, many people recommend always including ".ConfigureAwait(false)" when you use await, like this:

await Task.Delay(1000).ConfigureAwait(false);

The "false" value is for the "continueOnCapturedContext" parameter and this parameter effectively overrides the synchronization context about what thread the work must continue on when the async work has completed.

If we changed our code to this:

public class HomeController

{

public ActionResult Index()

{

return View(

GetTitleAsync().Result

);

}

private async Task<string> GetTitleAsync()

{

// This Task.Delay call simulates an async call that might go off to the

// database or other external service

await Task.Delay(1000).ConfigureAwait(false);

return "Hello!";

}

}

.. then the chain of events goes more like this:

- Thread "A" would be given to the request to run on and "Index" would be called

- Thread "A" would call "GetTitleAsync" and get a Task<string> reference

- Thread "A" would then request the ".Result" property of that task and would block until the task completed

- The "Task.Delay" call would complete and .NET would try to continue the "GetTitleAsync" work

- Because we used ".ConfigureAwait(false)", we are not restricted in terms of where can continue the "GetTitleAsync" work and so that will be done on Thread "B"

- The work for Thread "B" is simply to complete the Task<string> by setting its result to "Hello!" (Thread "B" does this and then it is released back to the ThreadPool)

- Since the Task<string> has completed, Thread "A" is no longer blocking on the ".Result" access and it can carry on with its work and return the ActionResult from the method

The good news here is that this solves the problem - there is no longer a deadlock that can occur!

The bad news is that you must remember to add ".ConfigureAwait(false)" to your await calls. If you forget then there is a chance that your code will result in an application hang and you won't find out until runtime. I don't like this because one of the reasons that I enjoy C# as a strongly-typed language is that the compiler can catch so many mistakes and I don't have to wait until runtime to find problems much of the time. One way to make life easier on this front is to help the compiler help you by installing an analyser, such as the ConfigureAwaitChecker.Analyzer. Installing this should result in you getting warnings in Visual Studio if you don't include ".ConfigureAwait(false)" after any await.

Another possible (and subjective) downside to this approach is that it makes the code "noisier" - if ".ConfigureAwait(false)" should be used almost every time you use "await" then shouldn't it be the default behaviour and it be the case that you should have to include extra code if you don't want that behaviour? You may not agree with me but it feels like an extra burden that I'd rather live without.

Instead, we could consider..

Approach three: Disabling the synchronization context before calling async code. The .NET environment allows the host to specify its own synchronization context but it also allows any code to specify a particular context. We could use this to our advantage by doing something like this:

public class HomeController

{

public ActionResult Index()

{

// Get a reference to whatever the current context is, so that we can set

// it back after the async work is done

var currentSyncContext = SynchronizationContext.Current;

string result;

try

{

// Set the context to null so that any restrictions are removed that

// relate to what threads async code can continue on

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(null);

// Block this thread until the async work is complete

result = GetTitleAsync().Result;

}

finally

{

// Set the context back to whatever it was before

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(currentSyncContext);

}

return View(result);

}

private async Task<string> GetTitleAsync()

{

// This Task.Delay call simulates an async call that might go off to the

// database or other external service

await Task.Delay(1000);

return "Hello!";

}

}

This means that we don't have to use ".ConfigureAwait(false)" and we still don't get any deadlocks. We can include code like this at the boundary where non-async code calls async code and then we won't have to worry about whether the async code includes any await calls that do not specify ".ConfigureAwait(false)".

You wouldn't want to include this extra code every time that you called async code from non-async code and so it would make sense to encapsulate the logic in a method. Something like this:

public class HomeController : Controller

{

public ActionResult Index()

{

return View(

AsyncCallHelpers.WaitForAsyncResult(GetTitleAsync())

);

}

private async static Task<string> GetTitleAsync()

{

// This Task.Delay call simulates an async call that might go off to the

// database or other external service

await Task.Delay(1000);

return "Hello!";

}

}

public static class AsyncCallHelpers

{

/// <summary>

/// Avoid the 'classic deadlock problem' when blocking on async work from non-async

/// code by disabling any synchronization context while the async work takes place

/// </summary>

public static T WaitForAsyncResult<T>(Task<T> work)

{

var currentSyncContext = SynchronizationContext.Current;

try

{

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(null);

return work.Result;

}

finally

{

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(currentSyncContext);

}

}

}

I think that this is quite an elegant solution and makes for clear code (it is hopefully fairly clear to a reader of the code that there is something interesting going on at the non-async / async boundary and there is a nice summary comment explaining why).

A variation on this theme is..

Approach four: Use a custom INotifyCompletion implementation. When Task/Task<T> was added to .NET along with async / await, the design included ways to override how awaiting a task should be handled and this gives us another way to remove the synchronization context for async work. We can take advantage of this facility by doing something like this:

public class HomeController : Controller

{

public ActionResult Index()

{

return View(

GetTitleAsync().Result

);

}

private async static Task<string> GetTitleAsync()

{

await new SynchronizationContextRemover();

// This Task.Delay call simulates an async call that might go off to the

// database or other external service

await Task.Delay(1000);

return "Hello!";

}

}

/// <summary>

/// This prevents any synchronization context from affecting what happens within

/// an async method and so we don't need to worry if a non-async caller wants to

/// block while waiting for the result of the async method

/// </summary>

public struct SynchronizationContextRemover : INotifyCompletion

{

public bool IsCompleted => SynchronizationContext.Current == null;

public void OnCompleted(Action continuation)

{

var prevContext = SynchronizationContext.Current;

try

{

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(null);

continuation();

}

finally

{

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(prevContext);

}

}

public SynchronizationContextRemover GetAwaiter() => this;

public void GetResult() { }

}

(This code comes from the article "An alternative to ConfigureAwait(false) everywhere")

This has the same effect as the previous approach - it removes any synchronization context until the async work has completed - but there is an important difference in how it is implemented:

- When disabling the synchronization context before calling async code, the extra code is included in the non-async code that is calling the async code

- When we use a custom INotifyCompletion implementation, the extra code is included in the async code and the non-async calling code does not need to be changed

I prefer these two approaches and choosing which of them to use comes down to what code I'm writing and what code I'm integrating with. For example:

- If I was writing the non-async code and I needed to call into a trusted and battle-tested async library then I might be tempted to do nothing at all because I would expect such a library to follow recommended practices such as using ".ConfigureAwait(false)" internally

- If I was writing non-async code that had to call into async code that I was less confident about then I would call it using "AsyncCallHelpers.WaitForAsyncResult" to be sure that nothing was going to go awry

- Note: This only applies to non-async code that will be hosted in an environment that uses a synchronization context that I need to be worried about (such as ASP.NET or WinForms but not Console Applications or Windows Services)

- If I was writing async code that might be called from different environments (where an awkward synchronization context might come into play), then I would use the SynchronizationContextRemover approach at the public boundaries (so that I wouldn't need to specify ".ConfigureAwait(false)" every time that I await something in my code)

Two more "solutions" to round out the post

To quickly recap, the commonly-suggested recommendations for avoiding the 'classic deadlock problem' are:

- Don't mix async and non-async code

- Always use ".ConfigureAwait(false)"

- Disabling the synchronization context before calling async code

- Use a custom INotifyCompletion implementation

.. but there are two others that I think are worthy of mention.

Approach five: Use ASP.NET Core - the synchronization context that was used for previous versions of ASP.NET is not present in ASP.NET Core and so you don't have to worry if you're able to use it. If you already have a large application using non-Core ASP.NET that you are trying to introduce some async code into then whether or not this approach is feasible will likely depend upon your current code base and how much time you are willing to spend on migrating to ASP.NET Core.

Approach six: Use Task.Run - this is a workaround that I have seen in some Stack Overflow answers. We could change our example code to look like this:

public class HomeController

{

public ActionResult Index()

{

var result = Task.Run(async () => { return await GetTitleAsync(); }).Result;

return View(result);

}

private async Task<string> GetTitleAsync()

{

// This Task.Delay call simulates an async call that might go off to the

// database or other external service

await Task.Delay(1000);

return "Hello!";

}

}

This works because "Task.Run" will result in work being performed on a ThreadPool thread and so the thread that calls into GetTitleAsync will not be associated with an ASP.NET synchronization context and so the deadlock won't occur.

It feels more like a workaround, rather than a real solution, and I don't like the way that it's not as obvious from reading the code why it works. It could be wrapped in a method like "AsyncCallHelpers.WaitForAsyncResult" so that comments could be added to explain why it's being used but I feel like if you were going to do that then you would be better to use one of the more explicit approaches (such as the "AsyncCallHelpers.WaitForAsyncResult" method shown earlier). I have included it in this post only for completeness and because it is presented as a solution sometimes!

Further reading

To try to keep this post focused, I've skipped over and simplified some of the details involved in how async and await work. I think that it's testament to the C# language designers that it can be such a complicated topic while the code "just works" most of the time, without you having to be aware of how it works all the way down.

If you would like to find more then I would recommend the following articles. I read and re-read all of them while writing this to try to make sure that I wasn't over-simplifying too much (and to try ensure that I didn't say anything patently false!)..

Stephen Cleary's "There is no thread"

Also Stephen Cleary's (this time published on msdn.microsoft.com) "Parallel Computing - It's All About the SynchronizationContext"

Dixin's "Understanding C# async / await: The Awaitable-Awaiter Pattern"

Posted at 20:09

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)