TypeScript classes for (React) Flux actions

I've been playing with React over the last few months and I'm still a fan. I've followed Facebook's advice and gone with the "Flux" architecture (there's so many good articles about this out there that I couldn't even decide which one to link to) but I've been writing the code using TypeScript. So far, most of my qualms with this approach have been with TypeScript rather than React; I don't like the closing-brace formatting that Visual Studio does and doesn't let you change, its generics system is really good but not quite as good as I'd like (not as good as C#'s, for example, and I sometimes wish generic type params were available at runtime for testing but I do understand why they're not). I wish the "Allow implicit 'any' types" option defaulted to unchecked rather than checked (I presume this is to encourage "gradual typing" but if I'm using TypeScript I'd rather go whole-hog).

But what I thought were going to be the big problems with it haven't been, really - type definitions and writing the components (though I am using a bit of a hack that relies upon an older version of React - I'm hoping to change this when 0.13 comes out and introduces better support for ES6 classes).

Writing the components in "pure" TypeScript results in more code than jsx.. it's not the end of the world, but something that would combine the benefits of both (strong typing and succint jsx format) would be wonderful. There are various possibilities that I believe people are looking into, from modifying the TypeScript compiler to support jsx to the work that Facebook themselves are doing around "Flow" which "Adds static typing to JavaScript to improve developer productivity and code quality". Neither of these are ready for me to integrate into Visual Studio, which I'm still using since I like it so much for my other development work.

What I want to talk about today, though, is one of the ways that TypeScript's capabilities can make a nice tweak to how the Flux architecture may be realised. Hopefully the following isn't blindly obvious and well-known, I failed to find any other posts out there explaining it so I'm going to try to take credit for it! :)

As recommended and apparently done by everyone..

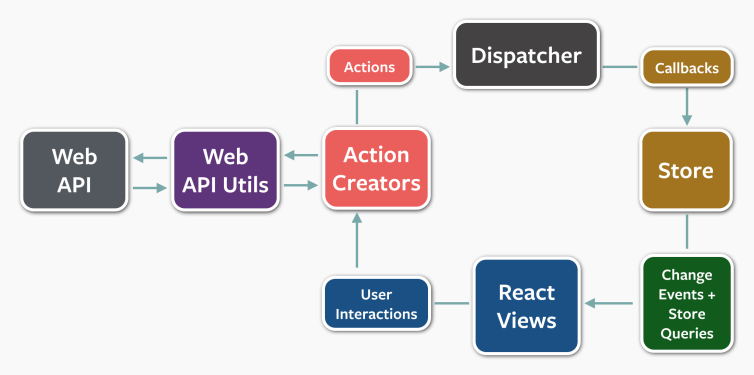

Here's the diagram that everyone who's looked into Flux will have seen many times before (since I've nicked it straight from the React blog's post about it) -

In the middle are the "Action Creators", which create objects that represent actions (and any associated data) so that the Dispatcher has something to send out. Stores listen for these actions - checking whether a given action is one that they're interested in and extracting the information from it as required.

As a concrete example, here is how actions are created in Facebook's "TODO" example (from their repo on GitHub):

/*

* Copyright (c) 2014, Facebook, Inc.

* All rights reserved.

*

* This source code is licensed under the BSD-style license found in the

* LICENSE file in the root directory of this source tree. An additional grant

* of patent rights can be found in the PATENTS file in the same directory.

*

* TodoActions

*/

var AppDispatcher = require('../dispatcher/AppDispatcher');

var TodoConstants = require('../constants/TodoConstants');

var TodoActions = {

/**

* @param {string} text

*/

create: function(text) {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_CREATE,

text: text

});

},

/**

* @param {string} id The ID of the ToDo item

* @param {string} text

*/

updateText: function(id, text) {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_UPDATE_TEXT,

id: id,

text: text

});

},

/**

* Toggle whether a single ToDo is complete

* @param {object} todo

*/

toggleComplete: function(todo) {

var id = todo.id;

if (todo.complete) {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_UNDO_COMPLETE,

id: id

});

} else {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_COMPLETE,

id: id

});

}

},

/**

* Mark all ToDos as complete

*/

toggleCompleteAll: function() {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_TOGGLE_COMPLETE_ALL

});

},

/**

* @param {string} id

*/

destroy: function(id) {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_DESTROY,

id: id

});

},

/**

* Delete all the completed ToDos

*/

destroyCompleted: function() {

AppDispatcher.dispatch({

actionType: TodoConstants.TODO_DESTROY_COMPLETED

});

}

};

module.exports = TodoActions;

Every action has an "actionType" property. Some have an "id" property, some have a "text" property, some have both, some have neither. Other examples I've seen follow a similar pattern where the ActionCreator (or ActionCreators, since sometimes there are multiple - as in the chat example in that same Facebook repo) is what is responsible for knowing how data is represented by each action. Stores assume that if the "actionType" is what they expect then all of the other properties they expect to be associated with that action will be present.

Here's a snippet I've taken from another post:

var action = payload.action;

switch(action.actionType){

case AppConstants.ADD_ITEM:

_addItem(payload.action.item);

break;

case AppConstants.REMOVE_ITEM:

_removeItem(payload.action.index);

break;

case AppConstants.INCREASE_ITEM:

_increaseItem(payload.action.index);

break;

case AppConstants.DECREASE_ITEM:

_decreaseItem(payload.action.index);

break;

}

Some actions have an "item" property, some have an "index". The ActionCreator was responsible for correctly populating data appropriate to the "actionType".

Types, types, types

When I first start writing code like this for my own projects, it felt wrong. Wasn't I using TypeScript so that I had a nice reassuring type safety net to protect me against my own mistakes?

Side note: For me, this is one of the best advantages of "strong typing", the fact the compiler can tell me if I've mistyped a property or argument, or if I want to change the name of one of them then the compiler can change all references rather than it being a manual process. The other biggie for me is how beneficial it can be in helping document APIs (both internal and external) - for other people using my code.. or just me when it's been long enough that I can't remember all of the ins and outs of what I've written! These are more important to me than getting worried about whether "static languages" can definitely perform better than "dynamic" ones (let's not open that can of worms).

Surely, I asked myself, if these objects have properties that vary based upon an "actionType" magic string, these would be better expressed as actual types? Like classes?

Working from the example above, there would be classes such as:

class AddItemAction {

constructor(private _index: number) { }

get index() {

return this._index;

}

}

export = AddItemAction;

I'm a fan of the AMD pattern so I would have a separate file per action class and then explicitly "import" (in TypeScript terms) them into Stores that reference them. The main reason I'm leaning towards the AMD pattern is that you can use require.js to load in the script required to render the first "page" and then dynamically load in additional script as more functionality of the application is used. This should avoid the risk of the dreaded multi-megabyte initial download (and the associated delays). I'm still proving this to myself - it's looking very promising so far but I haven't written any multi-megabyte applications yet!

I also like things to be immutable, otherwise the above could have been shortened even further to:

class AddItemAction {

constructor(public index: number) { }

}

export = AddItemAction;

But, technically, this could lead to one Store changing data in an action, which could affect what another Store does with the data. An effect that would only happen if that first Store received the action before the second one. Yuck. I don't imagine anyone would want to do something like that but immutability means that it's not even possible, even by accident (especially by accident).

So if there were classes for each action then the listening code would look more like this:

if (action instanceof AddItemAction) {

this._addItem(action);

}

if (action instanceof RemoveItemAction) {

this._removeItem(action);

}

if (action instanceof IncreaseItemAction) {

this._increaseItem(action);

}

if (action instanceof DecreaseItemAction) {

this._decreaseItem(action);

}

I prefer to have the functions receive the actual action. The AddItemAction instance is passed to the "_addItem" function, for example, rather than just the "index" property value - eg.

private _addItem(action: AddItemAction) {

// Do whatever..

}

This is at least partly because it makes the type comparing code more succinct - the "action" reference will be of type "any" (as will be seen further on in this post) and so TypeScript lets us pass it straight in to methods such as _addItem since it presumes that if it's "any" then it can be used anywhere, even as an function argument that has a specific type annotation. The type check that is made before _addItem is called gives us the confidence that the data is appropriate to pass to _addItem, the TypeScript compiler will then happily take our word for it.

Update (25th February 2015): A couple of people in the comments suggested that the action property on the payload should implement an interface to "mark" it as an action. This is something I considered originally but I dismissed it and I think I'm going to continue to dismiss it for the following reason: the interface would be "empty" since there is no property or method that all actions would need to share. If this were C# then every action class would have to explicitly implement this "empty interface" and so we could do things like search for all implementation of IAction within a given project or binary. In TypeScript, however, interfaces may be implemented implicitly ("TypeScript is structural"). This means that any object may be considered to have (implicitly) implemented IAction, if IAction is an empty interface. And this means that there would be no reliable way to search for implementations of IAction in a code base. You could search for classes that explicitly implement it, but if you have to rely upon people to follow the convention of decorating all action classes with a particular interface then you might as well rely on a simpler convention such as keeping all actions within files under an "action" folder.

Server vs User actions

Another concept that this works well with is one that I think I first read at Atlassian's blog: Flux Step By Step - the idea of identifying a given action as originating from a view (from a user interaction, generally) or from the server (such as an ajax callback).

They suggested the use of an AppDispatcher with two distinct methods, each wrapping an action up with an appropriate "source" value -

var AppDispatcher = copyProperties(new Dispatcher(), {

/**

* @param {object} action The details of the action, including the action's

* type and additional data coming from the server.

*/

handleServerAction: function(action) {

var payload = {

source: 'SERVER_ACTION',

action: action

};

this.dispatch(payload);

},

/**

* @param {object} action The details of the action, including the action's

* type and additional data coming from the view.

*/

handleViewAction: function(action) {

var payload = {

source: 'VIEW_ACTION',

action: action

};

this.dispatch(payload);

}

});

Again, these are "magic string" values. I like the idea, but TypeScript has the tools to do better.

I have a module with an enum for this:

enum PayloadSources {

Server,

View

}

export = PayloadSources;

and then an AppDispatcher of my own -

import Dispatcher = require('third_party/Dispatcher/Dispatcher');

import PayloadSources = require('constants/PayloadSources');

import IDispatcherMessage = require('dispatcher/IDispatcherMessage');

var appDispatcher = (function () {

var _dispatcher = new Dispatcher();

return {

handleServerAction: function (action: any): void {

_dispatcher.dispatch({

source: PayloadSources.Server,

action: action

});

},

handleViewAction: function (action: any): void {

_dispatcher.dispatch({

source: PayloadSources.View,

action: action

});

},

register: function (callback: (message: IDispatcherMessage) => void): string {

return _dispatcher.register(callback);

},

unregister: function (id: string): void {

return _dispatcher.unregister(id);

},

waitFor: function (ids: string[]): void {

_dispatcher.waitFor(ids);

}

};

} ());

// This is effectively a singleton reference, as seems to be the standard pattern for Flux

export = appDispatcher;

The IDispatcherMessage is very simple:

import PayloadSources = require('constants/PayloadSources');

interface IDispatcherMessage {

source: PayloadSources;

action: any

}

export = IDispatcherMessage;

This allows me to listen for actions with code thusly -

AppDispatcher.register(message => {

var action = message.action;

if (action instanceof AddItemAction) {

this._addItem(action);

}

if (action instanceof RemoveItemAction) {

this._removeItem(action);

}

// etc..

Now, if I come across a good reason to rename the "index" property on the AddItemAction class, I can perform a refactor action that will fix it everywhere. If I don't use the IDE to perform the refactor, and just change the property name in one place, then I'll get TypeScript compiler errors about an "index" property that no longer exists.

The mysterious Dispatcher

One thing I skimmed over in the above is what the "third_party/Dispatcher/Dispatcher" component is. The simple answer is that I took the Dispatcher.js file from the Flux repo and messed about with it a tiny bit to get it to compile as TypeScript with my preferred disabling of the option "Allow implicit 'any' types". In case this is a helpful place for anyone to start, I've put the result up on pastebin as TypeScript Flux Dispatcher, along with the required support class TypeScript Flux Dispatcher - invariant support class.

Final notes

I'm still experimenting with React and Flux but this is one of the areas that I've definitely been happy with. I like the Flux architecture and the very clear way in which interactions are handled (and the clear direction of flow of information). Describing the actions with TypeScript classes feels very natural to me. It might be that I start grouping multiple actions into a single module as my applications get bigger, but for now I'm fine with one per file.

The only thing I'm only mostly happy with is my bold declaration in the AppDispatcher class; "This is effectively a singleton reference, as seems to be the standard pattern for Flux". It's not the class that's exported from that module, it's an instance of the AppDispatcher which is used by everything in the app. This makes sense in a lot of ways, since it needs to be used in so many places; there will be various Stores that register to listen to it but there are likely to be many, many React components, any one of which could accept some sort of interaction that requires an action be created (and so be sent to the AppDispatcher). One alternative approach would be to use dependency injection to pass an AppDispatcher through every component that might need it. In fact, I did try that in one early experiment but found it extremely cumbersome, so I'm happy to settle for what I've got here.

However, the reason (one of, at least!) that singletons got such a bad name is that they can making unit testing very awkward. I'm still in the early phases of investigating what I think is the best way to test a React / Flux application (there are a lot of articles out there explaining good ways to tackle it and I'm trying to work my way through some of their ideas). One thing that I'm contemplating, particularly for testing simple React components, is to take advantage of the fact that I'm using AMD everywhere and to try changing the require.js configuration for tests - for any given test, when an AppDispatcher is requested, some sort of mock object could be provided in its place.

This would have the two main benefits that it could expose convenient methods to confirm that a particular action was raised following a given interaction (which may be the main point of that particular test) but also that there would be no shared state that needs resetting between tests; each test would provide its own AppDispatcher stand-in. I've not properly explored this yet, it's still in the idea phase, but I think it also has promise. And - if it all goes to plan - it's another reason way for me to convince myself that AMD loading within TypeScript is the way to go!

Posted at 22:24

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)