WCF CORS (plus JSON & REST) - Complete Example

Someone asked me the other day if I knew how to enable CORS (Cross Origin Resource Sharing for a WCF service. This is commonly used to enable AJAX requests from a web page to retrieve content from a domain outside of the domain that delivered the page that the JavaScript is executing from. For a number of reasons, this is not allowed by default by web browsers but the security measure may be relaxed in modern browsers if the data is delivered with certain headers in the response:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Request-Method: POST,GET,PUT,DELETE,OPTIONS

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: X-Requested-With,Content-Type

There's information about this on the "Enable CORS" website: CORS on WCF.

My friend had found this information and struggled to make it work. It looked like it should be simple enough to me, so I thought I'd give it a go.

I did not find it simple.

But I cracked it in the end! So I'm recording the necessary steps here for posterity.. or for when I might need it in the future. Truth be told, there's no one thing that's mind-blowingly difficult, it's just a case of trying to remember how WCF ties things together when you've not dealt with it for a little while.

Modern WCF configuration - so easy to get started!

When Visual Studio 2010 and .net 4 were released, one of the things they introduced was cleaner web.config files that used nice defaults to prevent the bloat that had been added over time. (ScottGu talked about it at Clean Web.Config Files - there he uses a web application rather than a WCF service as an example, but works was done on the WCF side too).

The initial web.config you get when you go to New Project / WCF / WCF Service Application in VS 2013 is:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<configuration>

<appSettings>

<add key="aspnet:UseTaskFriendlySynchronizationContext" value="true" />

</appSettings>

<system.web>

<compilation debug="true" targetFramework="4.5" />

<httpRuntime targetFramework="4.5"/>

</system.web>

<system.serviceModel>

<behaviors>

<serviceBehaviors>

<behavior>

<serviceMetadata httpGetEnabled="true" httpsGetEnabled="true"/>

<serviceDebug includeExceptionDetailInFaults="false"/>

</behavior>

</serviceBehaviors>

</behaviors>

<protocolMapping>

<add binding="basicHttpsBinding" scheme="https"/>

</protocolMapping>

<serviceHostingEnvironment aspNetCompatibilityEnabled="true" multipleSiteBindingsEnabled="true"/>

</system.serviceModel>

<system.webServer>

<modules runAllManagedModulesForAllRequests="true"/>

<directoryBrowse enabled="true"/>

</system.webServer>

</configuration>

(I removed a couple of XML comments to make it more succint but didn't change anything else).

This is great when you want to get cracking with the default settings but when you want to apply customisations it's not always clear where to start. The Enable CORS documentation says that you have to

- Create a couple of classes

- "Register new behavior in web.config"

- "Add new behavior to endpoint behavior configuration"

- "Configure endpoint"

I'm going to take an example project and apply all of these steps, explaining what each one means (largely because when I first read them, I couldn't remember what each one meant in the context of WCF configuration!).

If you want to follow along at home, create a new WCF Service Application project and call it "CORSExample". This will create the files IService1.cs, Service1.svc and Web.config. Change IService1.cs's content to

using System.ServiceModel;

using System.ServiceModel.Web;

namespace CORSExample

{

[ServiceContract]

public interface IService1

{

[OperationContract]

ServiceResponse GetData(string value);

}

}

and change Service1.svc to

using System;

using System.ServiceModel.Activation;

namespace CORSExample

{

public class Service1 : IService1

{

public ServiceResponse GetData(string value)

{

return new ServiceResponse

{

ReceivedAt = DateTime.Now,

Value = string.Format("You entered: {0}", value)

};

}

}

}

Then add a new file "ServiceResponse.cs" and set its content to

using System;

using System.Runtime.Serialization;

namespace CORSExample

{

[DataContract]

public class ServiceResponse

{

[DataMember]

public DateTime ReceivedAt { get; set; }

[DataMember]

public string Value { get; set; }

}

}

This gives us the outline of a very basic service. You could start this project up and then create a WCF client to communicate with it. It's the most basic example you can likely imagine that takes any form of input and returns a non-primitive-type response. I wanted a "complex response type" to show how responses may be JSON-serialised very easily.. but that comes later, we're not returning JSON at the moment!

Laying the groundwork

Starting with the code on the CORS on WCF page, I took the two classes and combined them into one, removing some potentially-customisable code and replacing it with something that does just the job at hand. This results in a smaller surface area of exposed "new code" and means that I have less to confuse myself with!

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.ServiceModel;

using System.ServiceModel.Channels;

using System.ServiceModel.Configuration;

using System.ServiceModel.Description;

using System.ServiceModel.Dispatcher;

namespace CORSExample

{

public class CORSEnablingBehavior : BehaviorExtensionElement, IEndpointBehavior

{

public void AddBindingParameters(

ServiceEndpoint endpoint,

BindingParameterCollection bindingParameters) { }

public void ApplyClientBehavior(ServiceEndpoint endpoint, ClientRuntime clientRuntime) { }

public void ApplyDispatchBehavior(ServiceEndpoint endpoint, EndpointDispatcher endpointDispatcher)

{

endpointDispatcher.DispatchRuntime.MessageInspectors.Add(

new CORSHeaderInjectingMessageInspector()

);

}

public void Validate(ServiceEndpoint endpoint) { }

public override Type BehaviorType { get { return typeof(CORSEnablingBehavior); } }

protected override object CreateBehavior() { return new CORSEnablingBehavior(); }

private class CORSHeaderInjectingMessageInspector : IDispatchMessageInspector

{

public object AfterReceiveRequest(

ref Message request,

IClientChannel channel,

InstanceContext instanceContext)

{

return null;

}

private static IDictionary<string, string> _headersToInject = new Dictionary<string, string>

{

{ "Access-Control-Allow-Origin", "*" },

{ "Access-Control-Request-Method", "POST,GET,PUT,DELETE,OPTIONS" },

{ "Access-Control-Allow-Headers", "X-Requested-With,Content-Type" }

};

public void BeforeSendReply(ref Message reply, object correlationState)

{

var httpHeader = reply.Properties["httpResponse"] as HttpResponseMessageProperty;

foreach (var item in _headersToInject)

httpHeader.Headers.Add(item.Key, item.Value);

}

}

}

}

So add a file "CORSEnablingBehavior.cs" to the project and populate it with the above content.

This will, if we can attach it to the right thing in the right place at the right time, inject the response headers that we require.

To do so, we're going to have to add a "services" section to the web.config (within "system.serviceModel"). This config section is optional and so is not present in the bare bones config that Visual Studio created for us. We need to add it because we need to override some options -

<services>

<service name="CORSExample.Service1">

<endpoint address="" binding="webHttpBinding" contract="CORSExample.IService1" />

</service>

</services>

It's important that we specify the "webHttpBinding" since the CORSEnablingBehavior implementation will fail without it.

Having created this section, we must then fully populate it. The address attribute can stay blank (changing this alters the URLs that we make requests through - changing it to "something" would mean that requests from a client would have to POST their xml to "/Service1.svc/something" instead of just "/Service1.svc"). The contract attribute must match the type name (including namespace) of the interface precisely and the service name attribute must match the implementation class' type name (including namespace) precisely. If either of these are incorrect then Visual Studio is nice enough to draw your attention to this fact with a blue wobbly underline (the warning message "The Enumeration Constraint failed" could be friendlier, but this is basically what it means).

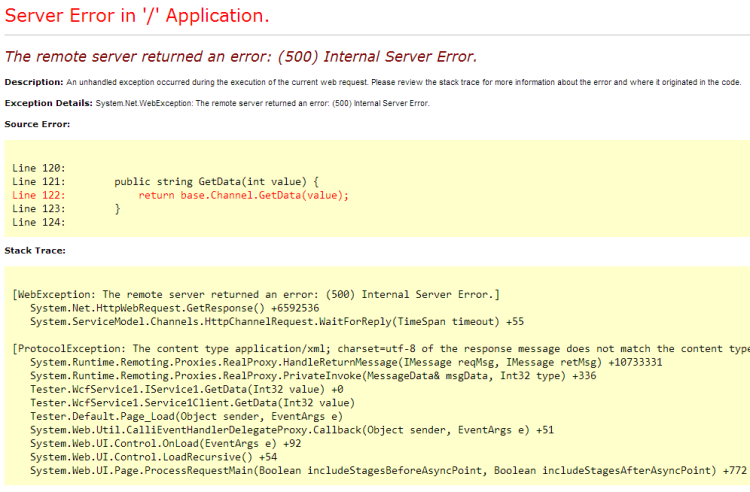

Now we need to configure the "webHttpBinding". The default is "basicHttpBinding" and that works out of the box. But if we tried to call the service having only made the change above, we'd be presented with a ProtocolException stating

The content type application/xml; charset=utf-8 of the response message does not match the content type of the binding (text/xml; charset=utf-8). If using a custom encoder, be sure that the IsContentTypeSupported method is implemented properly.

At least, that's what you'd get if you had a debugger attached to the process making the request. If you were making a request from a web application you would get a yellow screen of death showing something like

So we need to add another section (this time within "behaviors")

<endpointBehaviors>

<behavior>

<webHttp />

</behavior>

</endpointBehaviors>

If we go back to this fictional WCF client that I'm assuming you're testing the service with for now, you'll need to update the service reference since there's a different binding mechanism.

Then you're in for another treat. When configuring a Service Reference to a WCF service that uses basicHttpBinding, the client's web.config will be populated with information describing how to connect. Excellent, no problem. When the service uses webHttpBinding, however, it does not. This is explained in the post Mixing Add Service Reference and WCF Web HTTP endpoint does not work.

We can work around it for now by manually adding some content into the client's web.config (we'll be changing this service to work with JSON soon, and so probably not be consuming it through a generated WCF client - at that point we won't have to worry about this client web.config issue).

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!-- This is the CLIENT web.config (required to consume a WCF service that uses webHttpBinding) -->

<configuration>

<!-- This is default web.config content -->

<system.web>

<compilation debug="true" targetFramework="4.5" />

<httpRuntime targetFramework="4.5" />

</system.web>

<!-- This is the content that needs adding to consume the service-->

<system.serviceModel>

<behaviors>

<endpointBehaviors>

<behavior name="webhttp">

<webHttp/>

</behavior>

</endpointBehaviors>

</behaviors>

<bindings>

<webHttpBinding>

<binding name="WebHttpBinding_IService1" />

</webHttpBinding>

</bindings>

<client>

<endpoint name="WebHttpBinding_IService1" contract="CORSExample.IService1"

binding="webHttpBinding" bindingConfiguration="WebHttpBinding_IService1"

address="http://localhost:51192/Service1.svc"

behaviorConfiguration="webhttp" />

</client>

</system.serviceModel>

</configuration>

Note that the 51192 port in the endpoint address may vary for your test project. If you go to the project's properties page you should be able to find the port there.

Enables the CORS!

Right, we're really getting there now! Now we need to introduce the CORSEnablingBehavior class. In the service's web.config we need to add a new section (inside "system.servicemodel") -

<extensions>

<behaviorExtensions>

<add

name="crossOriginResourceSharingBehavior"

type="CORSExample.CORSEnablingBehavior, CORSExample, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral" />

</behaviorExtensions>

</extensions>

and then change the "endpointBehaviors" content we added before to

<endpointBehaviors>

<behavior>

<webHttp />

<crossOriginResourceSharingBehavior />

</behavior>

</endpointBehaviors>

Note: Doing this results in the "crossOriginResourceSharingBehavior" node being squiggly-underlined as an "invalid child element" - this is normal and may be ignored. Also note that the "crossOriginResourceSharingBehavior" string is arbitrary and may be any value so long as it is consistent between the two places in which it is used (the "name" attribute in the "behaviorExtensions" section and the actual node name in "endpointBehaviors"). However, the "type" attribute must match the type name (including namespace) precisely of the CORSEnablingBehavior class that we added earlier.

So now if you make a request from your WCF client the response will contain the required headers!

Success!!

Right now you only have my word for it, since Visual Studio doesn't show the raw messages that are passed in a WCF request. At times like this, I always turn to the trusty Fiddler. If you're not familiar with it, get familiar - it's fantastic! :) If you are familiar with it then you may well know that it doesn't register web requests made to "localhost". The easiest thing to do is to change the URL of the request so that "localhost" is replaced with "localhost.fiddler" (do this in the web.config of the client). Then Fiddler will show the details of the exchange. Just be aware that when Fiddler isn't connected that "localhost.fiddler" won't work.

As a recap, here's the complete WCF service web.config we've built for the "CORSExample" project:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<configuration>

<appSettings>

<add key="aspnet:UseTaskFriendlySynchronizationContext" value="true" />

</appSettings>

<system.web>

<compilation debug="true" targetFramework="4.5" />

<httpRuntime targetFramework="4.5"/>

</system.web>

<system.serviceModel>

<extensions>

<behaviorExtensions>

<add

name="crossOriginResourceSharingBehavior"

type="CORSExample.CORSEnablingBehavior, CORSExample, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral" />

</behaviorExtensions>

</extensions>

<behaviors>

<serviceBehaviors>

<behavior>

<serviceMetadata httpGetEnabled="true" httpsGetEnabled="true"/>

<serviceDebug includeExceptionDetailInFaults="true"/>

</behavior>

</serviceBehaviors>

<endpointBehaviors>

<behavior>

<webHttp />

<crossOriginResourceSharingBehavior />

</behavior>

</endpointBehaviors>

</behaviors>

<services>

<service name="CORSExample.Service1">

<endpoint address="" binding="webHttpBinding" contract="CORSExample.IService1" />

</service>

</services>

</system.serviceModel>

<system.webServer>

<modules runAllManagedModulesForAllRequests="true"/>

<directoryBrowse enabled="true"/>

</system.webServer>

</configuration>

A JSON endpoint

As I said at the start, I think that the most common use case for CORS-enabled services such as this is to make AJAX requests from JavaScript on a web page. To this end, it would be great if we didn't have to rely upon XML messages. It would be much better to be able to make the requests in some sort of RESTful manner (where the request is essentially represented by the URL, rather than a POST'd XML-serialised message) and to have the response expressed as JSON.

I'm going to leave thinking any deeper about the nitty gritty of what it means to be RESTful for another day (it can be a contentious issue!) and just make the current example communicate through a GET request that passes the "value" parameter as part of the URL.

This is actually extraordinarily easy at this point. The only change required is to the IService1 interface, it should now read

using System.ServiceModel;

using System.ServiceModel.Web;

namespace CORSExample

{

[ServiceContract]

public interface IService1

{

[WebGet(UriTemplate = "GetData/{value}", ResponseFormat = WebMessageFormat.Json)]

[OperationContract]

ServiceResponse GetData(string value);

}

}

This allows requests to be made such as

http://localhost:51192/Service1.svc/GetData/123

from the browser and for the response to be visible as serialised JSON

{"ReceivedAt":"\/Date(1403736100464+0100)\/","Value":"You entered: 123"}

Being in the browser, you don't even need Fiddler to see the response headers, you can use built-in developer tools and see that the headers are present.

Note that there was no change required to the service implementation nor to the response class - in the same way that it can be serialised to XML, the service can serialise the response to JSON.

There is one thing I maybe cheated on a little bit, though. My GetData method's argument is conveniently a string. If this is changed to anything else (an int, for example) then the service will not start up and throw an exception

Operation 'GetData' in contract 'IService1' has a path variable named 'value' which does not have type 'string'. Variables for UriTemplate path segments must have type 'string'.

But getting into all of the ins and outs of configuring requests for JSON are outside the scope of this post, I think. The aim was to enable CORS - and explain every part of what was required in doing so - and I think I've done that well enough for today. Enjoy!

Posted at 21:35

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)