React (and Flux) with Bridge.net

A couple of months ago I talked about using DuoCode to write React applications in C#. Since then I've been waiting for DuoCode to release information about their licensing and it's been a case of "in a few days" for weeks now, so I've been looking around to if there are any alternatives. A few weeks ago I tried out Bridge.net which is an open source C#-to-JavaScript translator. It's been public for about the same length of time as DuoCode and releases have been about one a month, similar to DuoCode.

Its integration with Visual Studio doesn't have a dedicated project type option and it doesn't support the debug-in-VS-when-running-in-IE facility that DuoCode has. The compiler doesn't seem to be quite as mature as DuoCode's, I've found a few bugs with it.. but I've reported them on their forum and they've addressed them all! I reported one bug in their forum and got a reply 14 minutes later saying that a fix had been pushed to GitHub - not bad service, that! :D

It currently uses something called NRefactory to parse C# but it's moving over to Roslyn soon*. It has recently acquired Saltarelle, another open source C#-to-JavaScript translator, so now has even more resources working on it. Enough introduction, though, you can find out more on their website if you want to!

* (It seems that with the release of Visual Studio 2015 and with Roslyn hitting the mainstream, Mono is another project moving over from using NRefactory to Roslyn for its C# parsing, read more from Miguel de Icaza at Roslyn and Mono - I'm excited by this since I think Roslyn is really going to open some doors for C#'s extensibility in the future; Bridge, Mono and DuoCode are all examples of this.. I've also used it for some simple code analysis in the past, see Locating TODO comments with Roslyn).

Getting started with Bridge.net

One of the nice things about DuoCode is that it made it extremely easy to get started - you can create a new DuoCode project and run it directly. I believe that the Visual Studio project system has historically been a bit of a mess so there must have been a lot of work gone into this to make it so seamless.

Bridge is a bit different, though. The simplest way to get started is to create a new Class Library project and add the Bridge.net NuGet package. This will not make it directly executable but it does add a demo.html file (under "Bridge/www") that you can browse to (either by locating it in the file system or by just right-clicking on it and selecting "View in Browser").

With DuoCode, you have the option of splitting your work over multiple projects - the "runnable" project can reference one or more other DuoCode projects and everything will still work just fine. The problem may come, however, if you want your main project to also host some .net code - you might want to create a Web API interface, for example, for the client-side code to call. But it's not possible to have a single project that translates some of its C# into JavaScript but also leaves some of it running as .net on the server.

In Bridge, I would recommend creating a standard ASP.net MVC web project and then adding one or more Bridge class libraries that copy their generated JavaScript into a location in the front end project. Bridge makes this easy as each project that pulls in the NuGet package creates a file "Bridge/bridge.json" which allows you to specify where the output JavaScript should go. (Currently, adding the NuGet package always pulls in the "getting started" folders, such as "Bridge/www", but I'm hopeful that a just-the-basics package will be available before too long - there's a forum thread I started about it on their site: Refining the NuGet package).

Working with React

I'm going to assume that you're familiar with React and, to make my life easier in writing this article as much as anything, I'm going to assume no knowledge of my DuoCode/React post. I've written before about writing React components in TypeScript and the same sort of concepts will be covered here - but, again, I'm going to assume you haven't read that and I'll start from scratch.

I'll start from the "React.render" method and work out from there. So first we need to write a binding to it. A binding is essentially a way to tell your C# at compile time about something that will be present at runtime.

To define "React.render" I'll create a class with an "Ignore" attribute on it - this instructs the translator that it does not need to generate any JavaScript from this C# class, it will be tied up to JavaScript already loaded in the browser (the assumption here, of course, is that the page that will execute the JavaScript translated from C# will also include the "React.js" library).

using Bridge.Html5;

namespace Bridge.React

{

[Name("React")]

[Ignore]

public static class React

{

[Name("render")]

public extern static void Render(ReactElement element, Element container);

}

}

Any references in the C# code to this class will try to access it within the "Bridge.React" namespace, so the C# compiler thinks its fully qualified class name is "Bridge.React.React"; in the JavaScript, though, this is not the case, the class is just called "React". The Bridge.net attribute "Name" allows us to tell the translator this - so when the C# code is translated into JavaScript, any references to "Bridge.React.React" will be rewritten to simply "React".

The same is applied to the method "Render" - in my C# code, I stick to the convention of pascal-casing function names, but the React library (like much other modern JavaScript) uses camel-cased function names.

Also note that the "Render" method does not have an implementation, it is marked as "extern". This is more commonly used in C# code to access unmanaged DLL functions but the bindings to JavaScript that we're describing are a similar mechanism - no body for this method needs to be included since the method itself is implemented elsewhere (in the React library, in this case). In order to be marked as "extern", a function must be decorated with an attribute (otherwise the compiler generates warnings). It doesn't matter what attribute is used, so the presence of the "Name" attribute is good enough.

For the function's arguments, the Element type is a Bridge.net class that represents DOM elements while the ReactElement is one that we must define as a binding -

namespace Bridge.React

{

[Ignore]

public sealed class ReactElement

{

private ReactElement() { }

}

}

This will never be explicitly instantiated, so it's a sealed class with a private constructor. It also does not need to be directly represented in the generated JavaScript, so it has an "Ignore" attribute on it too.

But, if ReactElement is never directly instantiated, how do we get instances of it? Well, there's the builtin React element creator functions (eg. "React.DOM.div", "React.DOM.span", etc..) and there are custom components. The builtin functions are nice and simple to writing bindings for, so I'll talk about them later and get to the interesting stuff..

Creating React components in Bridge.net

Since React 0.13 was released earlier this year, it has been possible to write JavaScript "classes" that may be used as React components. I write "classes" in quotes because a class is an ES6 concept but the code that transpilers emit (that take ES6 JavaScript and create equivalent code that will work on browsers that don't support ES6) is similar enough to the code generated by Bridge.net (and DuoCode) that we can use classes written in C# and rely upon the emitted JavaScript working nicely with React.. so long as a couple of rules are followed:

- These component classes will never be directly instantiated in code, so there should be no public constructor defined since it will never be called

- The way that they will be initialised is by the React library, via a "React.createElement" call - this will take the type of the component and will create some form of object based upon the component but according to its own rules (these are implementation details of the React library and should just be considered to be magic; trying to take advantage of any particular implementation detail is a good way to write a component that will break in a future version of React)

- The "createElement" call will also take a "props" reference, which will be set on the resulting React element - this is how a component is configured, rather than via the constructor (this "props" reference is private to the component and is guaranteed to be set as soon as the instance is created, so it's much more like "constructor dependency injection" than "property setter dependency injection")

- The components require a "render" method that returns a ReactElement

The surgery that React carries out to create components based upon classes is quite invasive, not only in how it new's-up an instance but also in how it investigates the "props" data. For each initialisation, it tears apart the provided props reference and creates a new object of its own devising, copying over the object properties from the original reference onto its own version.

This is problematic if the props reference you give is a class translated from C# since any methods (including property getters / setters) will be ignored by this process (React only copies properties that report true for "hasOwnProperty" and so ignores any class methods since these will be declared on the prototype of the class, not on the instance itself). The way to get around this is to wrap the props data in another object, one that has only a single field "Props", which is a reference back to the original props data - then, when React copies the properties around, this value will be migrated over without issue. The only annoyance is that this data must be unwrapped again before you can use it.

However, because I'm so good to you, I've pulled most of this together into an abstract class that you may use to derive custom component classes from -

using System;

namespace Bridge.React

{

public abstract class Component<TProps>

{

public static ReactElement New<TComponent>(TProps props)

where TComponent : Component<TProps>

{

if (props == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("props");

return Script.Call<ReactElement>(

"React.createElement",

typeof(TComponent),

new PropsWrapper { Props = props }

);

}

[Name("render")]

public abstract ReactElement Render();

[Name("unwrappedProps")]

protected TProps props

{

get { return wrappedProps.Props; }

}

[Name("props")]

private readonly PropsWrapper wrappedProps = null;

[ObjectLiteral]

private class PropsWrapper

{

public TProps Props;

}

}

}

There is a static "New" method that is used to create a ReactElement instance based upon the derived component class' type (using the "React.createElement" function). In the C# code, you call "New" with a "props" reference of the appropriate type and you get a ReactElement back. The "appropriate type" is the TProps generic type parameter of this base class. Making this a generic class means that calling code knows what data is required to create a new element instance (ie. a TProps instance) and the derived component class has a strongly-typed (again, TProps) reference to that props data.

There is a "Render" method that must be implemented on the derived class. It has a "Name" attribute to map my C# naming convention (of pascal-cased function names) onto React's convention (of camel-cased function names).

You can also see some messing about with the props data - the call to "React.createElement" uses a PropsWrapper which puts the "props" reference into a single property, as I described above. This will not be torn to shreds by React when it creates a new element. This data is then readable via the private "wrappedProps" property - since this is private to this base class, derived classes can not access it. They have to retrieve props data through the "props" property (which has type TProps, rather than PropsWrapper).

Now, there is some jiggery-pokery here, since the "wrappedProps" property has a "Name" attribute which indicates that this maps to a property called "props" in the JavaScript - but, as just described, this is a wrapper that keeps the real data safe from React's meddling. Similarly, the "props" property (which has "protected" accessibility and so is accessible by the derived type) has a "Name" attribute which maps it onto a property named "unwrappedProps" - this is not something that React has anything to do with, it's only to avoid clashing with the real "props" reference in the output JavaScript, while allowing C# code to be written that accesses a "props" property that is an unwrapped version of the props data.

Wow, that all sounds really confusing! But the upshot is that you can create a component as easily as:

using Bridge.React;

namespace BridgeExamples

{

public class WelcomeComponent : Component<WelcomeComponent.Props>

{

public static ReactElement New(Props props)

{

return New<WelcomeComponent>(props);

}

private WelcomeComponent() { }

public override ReactElement Render()

{

return DOM.Div(null, "Hi " + props.Name);

}

public class Props

{

public Props(string name)

{

Name = name;

}

public string Name { get; private set; }

}

}

}

Note that the "Render" method accesses "props.Name" directly - all of the wrapping / unwrapping is hidden away in the base class, the derived class is happily oblivious to all that PropsWrapper madness.

Also note that the constructor has been declared as private, which is important since these components should never be instantiated directly - they should only be brought into existence via that "React.createElement" function. To this end, a static "New" function is present (which calls the static "New" function on the base class).

(One more note - there's an attribute used by the Component base class that I haven't explained: "ObjectLiteral", I'll come back to this later..)

Bringing all this together, we could use this component in code such as:

React.Render(

WelcomeComponent.New(new WelcomeComponent.Props(name: "Ted")),

Document.GetElementById("main")

);

But before doing so, we'd better get back to the builtin React element creation functions..

Warning (July 2015): The code above will actually fail at runtime with the current version of Bridge (1.7) because of a bug I reported in their forums - however this has been fixed and will be included in the next release. I'm being optimistic and hoping that this article will be relevant in the future when this bug is just a distant memory :) Until the version after 1.7 is released, replace the line

return New<WelcomeComponent>(props);

with

return Component<WelcomeComponent.Props>.New<WelcomeComponent>(props);

and it will work fine. But in the future the less verbose version shown in the WelcomeComponent example will be safe.

Bindings for the regular DOM element functions

I skirted around the DOM functions such as React.DOM.div, React.DOM.span, etc.. earlier, so let's deal with them now.

In order to do so, I need to teach the type system a little trick. A component's "Render" method must always return a genuine ReactElement, but when specifying child elements for use in a component we must be able to provide either a ReactElement or a simple string. This is what was happening in the line from the WelcomeComponent:

return DOM.Div(null, "Hi " + props.Name);

The null value is for the attributes of the div (and is interpreted as "this div does not need any html attributes"), while the second argument is a string that is the sole child element of that div.

So we need a way to say that the child element argument value(s) for a DOM.div call may be either a ReactElement or a string. In some languages (such as TypeScript and F#), we could consider a union type, but here I'll cheat a bit and declare the "React.DOM.Div" function as:

namespace Bridge.React

{

[Name("React.DOM")]

[Ignore]

public static class DOM

{

[Name("div")]

public extern static ReactElement Div(

HTMLAttributes properties,

params ReactElementOrText[] children

);

and then define a new ReactElementOrText type -

namespace Bridge.React

{

[Ignore]

public sealed class ReactElementOrText

{

private ReactElementOrText() { }

[Ignore]

public extern static implicit operator ReactElementOrText(string text);

[Ignore]

public extern static implicit operator ReactElementOrText(ReactElement element);

}

This is another class with an "Ignore" attribute since it does not require any JavaScript to be generated for it, it's just to provide information to the C# compiler. It means that anywhere that a ReactElementOrText type is specified as an argument type, it is valid to provide either a ReactElement or a string. (The "Ignore" attributes on the functions are only present so that they may be identified as "extern" - as described earlier, an "extern" function must be decorated with an attribute of some kind).

The DOM class makes further of the "Name" attribute, ensuring that any accesses in C# to "Bridge.React.DOM" are replaced with just "React.DOM" in the generated JavaScript.

The final piece of the puzzle is the HTMLAttributes class -

using Bridge;

namespace Bridge.React

{

[ObjectLiteral]

public class HTMLAttributes

{

public string className;

}

}

As you can probably tell, this is not the full-featured React interface ("className" is not the only attribute that you can add to a div!) - at this point in time, it's still early days for the bindings that I'm writing for Bridge.net / React, so I've cut some corners. You'll see further down that I've not done all of the bindings for the DOM elements either! But hopefully this article is enough to get you up and running, then you can add to it yourself as you need more. (I'll also link to a repo at the end of the post..)

HTMLAttributes is another type that we don't directly want to include in the generated JavaScript. If we have the C# line -

return DOM.Div(new HTMLAttributes { className = "welcome" }, "Hello!");

we want this to be translated into the following:

return React.DOM.div({ className = "welcome" }, "Hello!");

This is idiomatic React-calling code.

Bridge.net has support to instruct the compiler to interpret class constructors in this way; through use of the "ObjectLiteral" attribute. When a class that is decorated with this attribute has its constructor called in C#, the generated JavaScript will just use the object literal notation rather than actually creating a full class instance. Note that this means that no JavaScript will be generated for that class, so the HTMLAttributes class does not appear in the JavaScript at any point.

We saw this "ObjectLiteral" attribute used earlier, on the Component base class - it was used for the wrapper around the props data. That wrapper is only used to nest the real "props" reference inside a property so that React's internals don't try to mess with it. It would be unnecessary to wrap that reference up inside a full class instance, it is more sensible for the generated JavaScript to be simply -

return React.createElement(TComponent, { props: props });

as opposed to something like

return React.createElement(

TComponent,

Bridge.merge(

new Bridge.React.Component.PropsWrapper$1(TProps)(),

{ props: props }

)

);

(which is what Bridge would emit if the PropsWrapper type did not have the "ObjectLiteral" attribute on it).

More DOM bindings..

As with the poorly-populated HTMLAttributes class, I also haven't written too many DOM element bindings yet. All I've got so far is "div", "h1", "input" and "span" - these have been enough for the sample projects I've started to experiment with integrating Bridge and React. However, the good news is that these few bindings illustrate enough principles that it should be clear how to write more as you need them.

The element creation functions that I have are as such:

using Bridge;

namespace Bridge.React

{

[Name("React.DOM")]

[Ignore]

public static class DOM

{

[Name("div")]

public extern static ReactElement Div(

HTMLAttributes properties,

params ReactElementOrText[] children

);

[Name("h1")]

public extern static ReactElement H1(

HTMLAttributes properties,

params ReactElementOrText[] children

);

[Name("input")]

public extern static ReactElement Input(

InputAttributes properties,

params ReactElementOrText[] children

);

[Name("span")]

public extern static ReactElement Span(

HTMLAttributes properties,

params ReactElementOrText[] children

);

}

}

"Span" and "H1" are just the same as "Div".

"Input" is interesting, though..

I started by following the same basic pattern for the InputAttribute type as you would find in the React bindings for TypeScript - there is an "onChange" callback which provides a FormEvent instance, which is a type that is derived from SyntheticEvent (names taken directly from the TypeScript binding).

The big difference is that the TypeScript bindings do not expose a "target" property on FormEvent to tie the event back to the element that it relates to, even though this information is available on the React event. I've exposed this information as the "target" property on FormEvent and exposed it as a known-type using the generic FormEvent class - the InputAttributes has an "onChange" type of Action<FormEvent<InputEventTarget>> which means that the type of "target" on the FormEvent will be an InputEventTarget. This allows us to query the input's value in the onChange callback, something that is a bit awkward with the TypeScript bindings.

(This is only possible because the React model exposes this information - bindings do not include their own logic, they only describe to the Bridge compiler how to interact with an existing library).

using Bridge;

namespace Bridge.React

{

[ObjectLiteral]

public class InputAttributes : HTMLAttributes

{

public Action<FormEvent<InputEventTarget>> onChange;

public string value;

}

[Ignore]

public class FormEvent<T> : FormEvent where T : EventTarget

{

public new T target;

}

[Ignore]

public class FormEvent : SyntheticEvent

{

public EventTarget target;

}

[Ignore]

public class SyntheticEvent

{

public bool bubbles;

public bool cancelable;

public bool defaultPrevented;

public Action preventDefault;

public Action stopPropagation;

public string type;

}

[Ignore]

public class InputEventTarget : EventTarget

{

public string value;

}

[Ignore]

public class EventTarget { }

}

There are obviously more properties that belong on the InputAttribute type (such as "onKeyDown", "onKeyPress", "onKeyUp" and many others) but for now I just wanted to write enough to prove the concept.

Flux

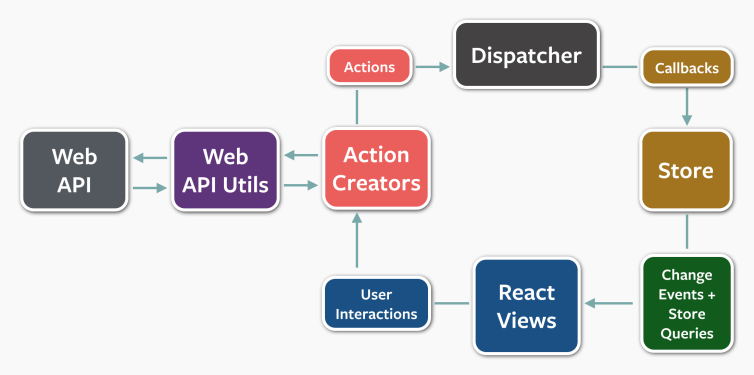

There's nothing that requires that you use the Flux architecture when you're using React, but I think it makes a huge amount of sense. When I was getting to grips with the React library, I found myself moving towards a similar solution before I'd read up on Flux - so when I did read about it, it was like someone had taken the vague ideas I'd had, tightened them all up and hammered out the rough edges.

The thing with it is, it really is just a set of architectural guidelines, it's not an actual library like React. It explains that you have "Stores" that manage state for the application - these Stores listen out for events that may require that they change their current state. This state is displayed using React, basically. The events that the Stores listen out for may be the result of a user interacting with the React elements or they may be raised by an API, informing the application that data that the user requested has arrived.

The piece in the middle is the "Dispatcher" and is effectively a queue that events can be pushed on (by user interactions or whatever else) and listened out for by the Stores - any events that a Store is not interested in, it ignores.

Asynchronous processes are quite easily handled in this arrangement because you can fire off an event as soon as an async request starts (in case some sort of loading spinner is desired) and then fire off another event when the data arrives (or when it times out or errors in some other way). Whatever happens, it's just events being raised and then received by interested Stores; Stores which alter their state and get React to re-render (if state changes were, in fact, required).

Using C# to write such a Dispatcher queue is really easy. Internally, it uses a C# event to make it easy to register (and then to call) as many listeners as required.

When compiled for the CLR, events are translated into IL that does all sorts of clever magic to behave well (and efficiently) in a multi-threaded environment. But here, it will be translated into JavaScript for the browser, which is single-threaded! So everything's very simple in the generated JavaScript and the C#.

using System;

namespace Bridge.React

{

public class AppDispatcher

{

private event Action<DispatcherMessage> _dispatcher;

public void Register(Action<DispatcherMessage> callback)

{

_dispatcher += callback;

}

public void HandleViewAction(IDispatcherAction action)

{

if (action == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("action");

_dispatcher(new DispatcherMessage(MessageSourceOptions.View, action));

}

public void HandleServerAction(IDispatcherAction action)

{

if (action == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("action");

_dispatcher(new DispatcherMessage(MessageSourceOptions.Server, action));

}

}

public class DispatcherMessage

{

public DispatcherMessage(MessageSourceOptions source, IDispatcherAction action)

{

if ((source != MessageSourceOptions.Server) && (source != MessageSourceOptions.View))

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("source");

if (action == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("action");

Source = source;

Action = action;

}

public MessageSourceOptions Source { get; private set; }

public IDispatcherAction Action { get; private set; }

}

public enum MessageSourceOptions { Server, View }

public interface IDispatcherAction { }

}

When you read about Flux events in JavaScript-based tutorials, you will see mention of "Actions" and "Action Creators". Actions will be JavaScript objects with some particular properties that describe what happened. Action Creators tend to be functions that take some arguments and generate these objects. In C#, I think it makes much more sense for Actions to be classes - that way the Action Creators are effectively just the Actions' constructors!

The AppDispatcher I've included code for above expects actions to be classes that share a common interface: IDispatcherAction. This is an "empty interface" and is just used to identify a class as being an action (you might want to search a solution for all Dispatcher actions, for example - you could do this by locating all implementations of IDispatcherAction). I wrote about this in terms of TypeScript earlier in the year and much of the same holds true here - so read more at TypeScript classes for (React) Flux actions if this sounds interesting (or confusing).

(Each action is wrapped in a DispatcherMessage, which describes it as being either a "Server" or "View" action. A Server action would tend to be a callback from an API event, as opposed to a key press that alters a particular editable field - which would be a View action. Differentiating between the two is a common practice but is optional, so you could drop the DispatcherMessage entirely if you wanted to and have the Dispatcher only deal with IDispatcherAction implementations. The only really compelling reasons I've encountered for differentiating between the two is that you might want to skip some forms of validation for Server actions since it may be presumed that data from the server is already known to be good).

A complete example

If you want to try any of this out (particularly if you don't feel like trying to piece it all together from the various code samples in this post!) then you can find a complete sample in a Bitbucket repo: ReactBridgeDotNet.

It's a web project that follows the structure I outlined at the top of this post - an MVC project to "host" and then Bridge projects to generate JavaScript from C#; one for the React bindings and another for the logic of the app.

The app itself is very, very simple - it's just a text box that doesn't want to be empty. If you clear it then you get a validation message. Any changes that you make to the input box are communicated to the app as Dispatcher actions, each of which results in a full re-render (in a complex app, React's virtual DOM ensures that this is done in an efficient manner, but in such a small example as this it's probably impossible to tell). Meanwhile, a label alongside the input box is updated with the current time - this is done to illustrate how non-user events (such as API data-retrieved events, for example) may be dealt with in exactly the same way as user events; they go through the Dispatcher and a Store deals with applying these channels to its internal state. Have fun!

Posted at 21:17

About

Dan is a big geek who likes making stuff with computers! He can be quite outspoken so clearly needs a blog :)

In the last few minutes he seems to have taken to referring to himself in the third person. He's quite enjoying it.

Recent Posts

- Hosting a DigitalOcean App Platform app on a custom subdomain (with CORS)

- (Approximately) correcting perspective with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part two)

- Finding the brightest area in an image with C# (fixing a blurry presentation video - part one)

- So.. what is machine learning? (#NoCodeIntro)

- Parallelising (LINQ) work in C#

Highlights

- Face or no face (finding faces in photos using C# and Accord.NET)

- When a disk cache performs better than an in-memory cache (befriending the .NET GC)

- Performance tuning a Bridge.NET / React app

- Creating a C# ("Roslyn") Analyser - For beginners by a beginner

- Translating VBScript into C#

- Entity Framework projections to Immutable Types (IEnumerable vs IQueryable)

Archives

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2019 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (2)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (3)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (2)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- October 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (4)

- December 2011 (7)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (3)